“Settler colonialism” is one of those buzzy phrases that seemed to suddenly appear and then spread in the last dozen years, breaking out of specialized fields like Indigenous Studies into a wider context and audience. So. where does the phrase come from, and what does it mean?

Historians Jeffrey Ostler and Nancy Shoemaker provide a useful introduction to settler colonialism in a forum on the topic in The William and Mary Quarterly, a journal of early American history. They note that the concept

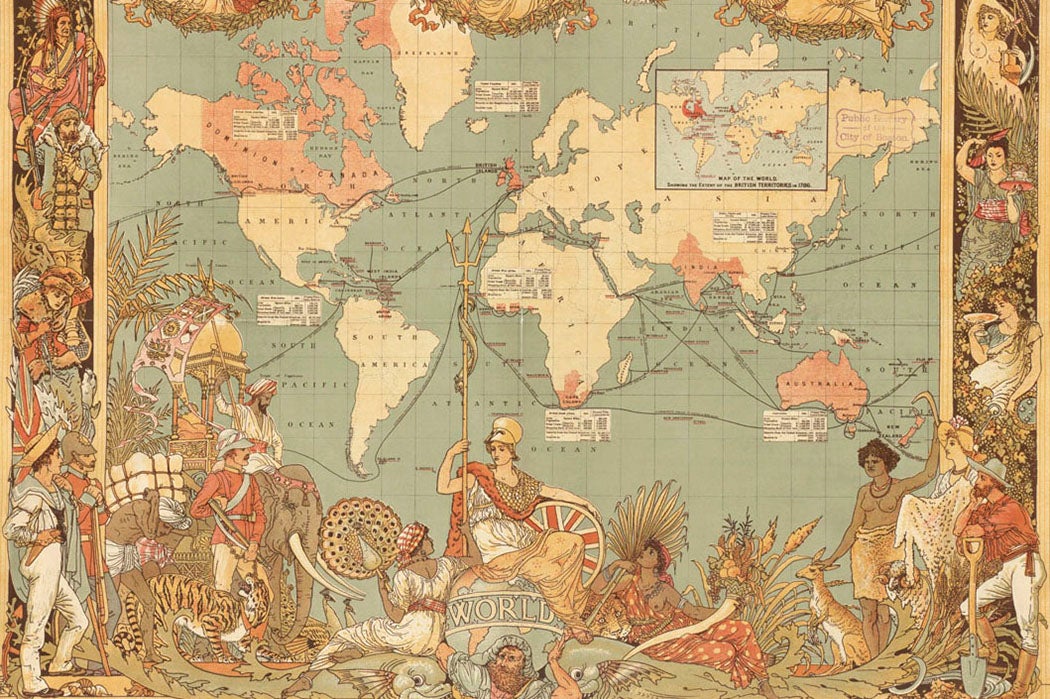

originally gained currency primarily through Australian scholars who wanted to differentiate between “ordinary” colonialism, in which colonizers exploited the labor and resources of colonized people, and settler colonialism, in which colonizers sought to take the lands of Indigenous people and eliminate them in one way or another.

They quote the Australian historian Patrick Wolfe, one of “most influential formulators” of the theory, on the “logic of elimination” inherent in the structure of settler colonialism. The colonized lands are conceptualized of as virgin or empty, or populated by savages and barbarians who amount to less-than-human types who must make way for the settlers. Inevitably, this leads to “outright genocide, removal, assimilation, and erasure” of Indigenous peoples and the transformation of the settlers and their descendants into the new “natives.”

“As settlers killed, removed, assimilated and marginalized Native peoples to wrest the land from them,” Ostler and Shoemaker write, “settlers justified their actions with racial logics and romanticized histories that separate Natives from their lands, both actually and figuratively, to privilege settler possession.”

More to Explore

Ayahs Abroad: Colonial Nannies Cross The Empire

Shoemaker notes in a separate article that the most successful of settler colonialists were the British—especially in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. Why the English and not the Dutch, Spanish, or French, the other major European colonial powers? What if, she asks, “settler colonial ideology” came out of the English reading of their own history in the early modern period, just as plantations—colonies—started being planted?

Invasion was fundamental to the telling of English history. Over a thousand years from 43 to 1066 CE, “a succession of foreigners arrived across the sea: Romans; German Angles, Jutes, and Saxons; Vikings; and Normans.” As early as 1611, English history was making much of how “various newcomers subdued, displaced, and usually assimilated whoever was in England before them, though sometimes it was the invaders, and not those they conquered, who did the assimilating.” Daniel Defoe, who was probably of Flemish descent (he added the fancy “De” to the family name) wrote in 1701, “Thus from a Mixture of all Kinds began, That Het’rogeneous Thing, An Englishman.”

English invasions continued into the early modern period, only now outwardly. By the early eighteenth century, English control over Ireland, Wales, and Scotland had been achieved by force or “heavy-handed negotiation,” writes Shoemaker. Why should the colonies being started further afield, starting in the Americas, be different?

Weekly Newsletter

In early English historiography, the Roman invasion of Britain was portrayed as beneficial, for it introduced the local barbarians “to civility and eventually to Christianity.” So, the English could think of themselves as the new Romans, bringing civilization and Christianity to the savages. And, in a nod to settler colonialism’s ideological erasure of Native peoples, the Britons found by the Romans were said to be not natives to begin with, but rather immigrants, too.

Shouldn’t there be, then, Shoemaker asks, a “long history” of settler colonialism?

“If Anglo-American attitudes toward North American Indians were not post-settlement inventions,” she writes, “but rather a marshaling of ideas deriving from an English cultural inheritance, then the history of English settler colonialism before 1492 might shed light on settler colonialism after 1492.”