Almost everyone has board games they remember from childhood—and usually, a few particular favorites. Perhaps you love sprawling strategy games that take hours or days; maybe a good classic round of chess or backgammon is just the ticket. Perhaps, like me, you have a soft spot for guessing words or pictures. Whatever your favorite game is, chances are it can trace its genealogy to some very aged relatives. Historians and social scientists have traced the history of gaming to include Nordic, Greek, Roman, Chinese, and pan-African games.

But as far as we’re concerned today, the nineteenth century was a pivotal time in terms of taking what had once been a way to pass the time and making it both commercial and ideological. It was during the 1800s that board games became a discrete and recognizable part of American amusement culture. This was not by accident. Changes in culture, media, manufacturing, communication, and industry opened homes and wallets to new ideas of game play. Shifts from an agrarian community culture to materialistic urban industry left their mark.

In their study of gaming and education in the long nineteenth century, David Wallace Adams and Victor Edmonds called out a few contributing factors, with increasing secularism near the top of the list. Colonial America and its antecedents may have been driven by religious ideas of propriety and success, but as the 1800s marched on, core American Protestantism had to stand up to individualism and a cultural hunger for self-made success. Quoting Richard M. Huber, who wrote on the American idea of success, they note that it wasn’t “not simply being rich or famous. It means attaining riches or achieving fame.” In this way morality came to be attached to success, foreshadowing the prosperity gospel and muscular Christianity. “A virtuous life, then,” write Adams and Edmonds, “was the path to a successful life.”

For a culture occupied with ideas of success and virtue, and whether they were both necessary in tandem, education operated as a means of cultural transmission, writes Jennifer Lynn Peterson. With childhood increasingly recognized as a distinct stage of life and education in the later nineteenth century, school texts and children’s books were one way to suggest to children a certain sort of morality and social grounding.

Games were another. After all, in a game, things are clearly laid out. Adams and Edmonds note that

[i]n the world of a game, the player knows just what he is after. At the same time success is not seized quickly; rather it is to be pursued slowly and orderly within the structured context of clearly defined rules. A game, then, creates a small world in which success and the means to attain it are crystal clear.

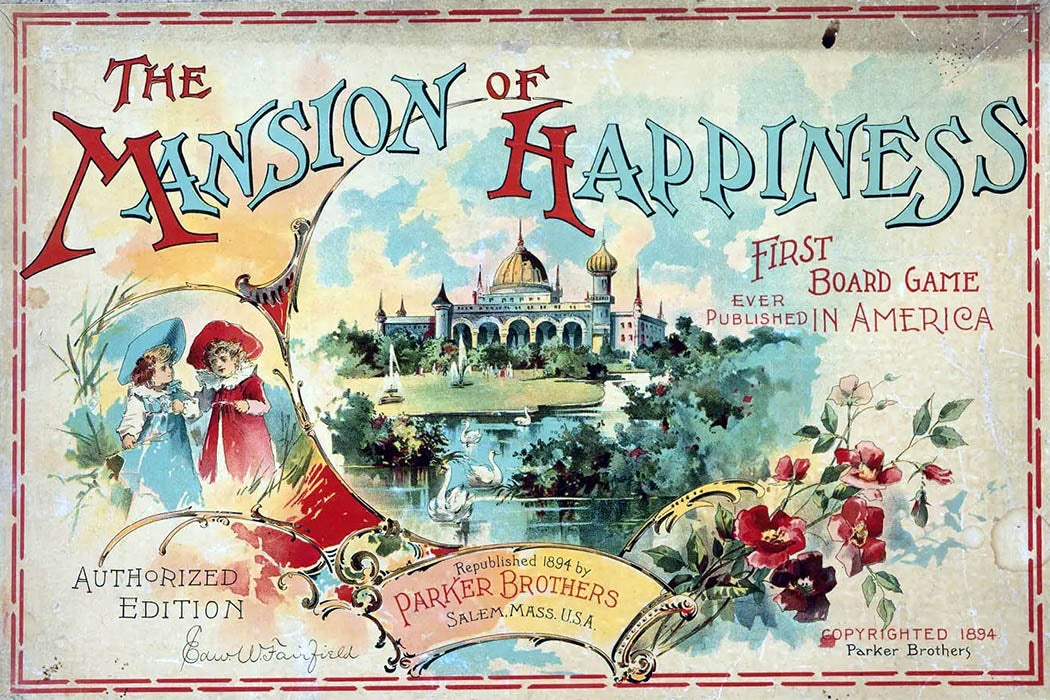

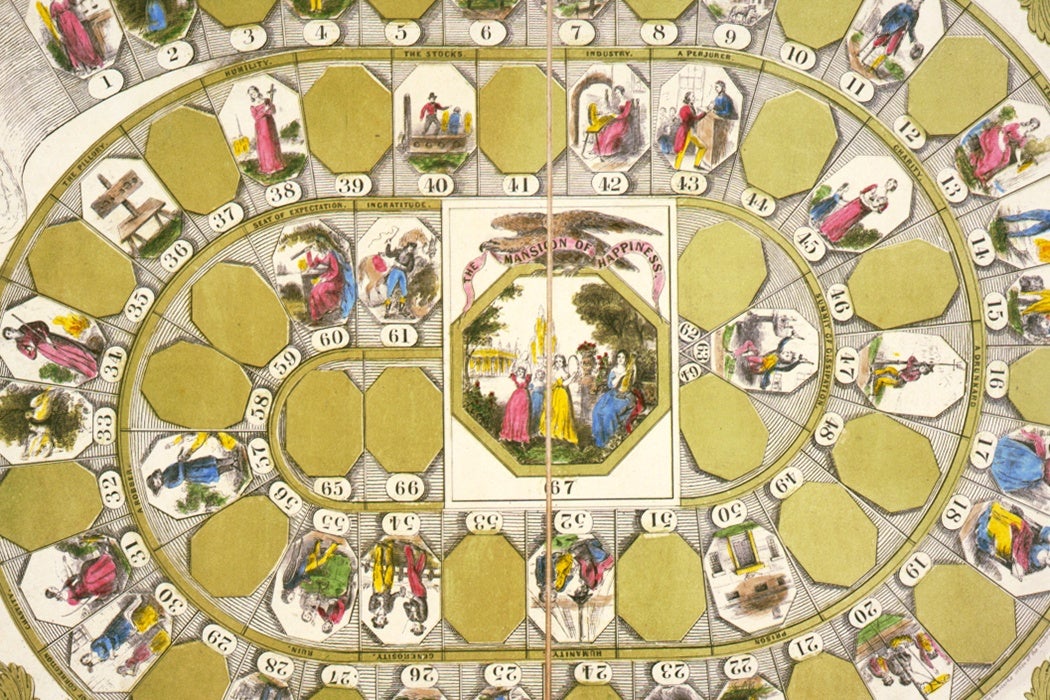

The first American commercial board game is usually thought to be The Mansion of Happiness, invented by Anne Abbott of Salem, Massachusetts. A riff on the traditional “racing game” mode in which players compete to move pieces along a path first (e.g., Parcheesi, backgammon, the ancient Egyptian senet), Mansion had a simple premise: players spun a “teetotum”—a spinner with numbers or pips on it—and moved their pieces around the decorated board. (A spinner was preferable to dice, which were associated with gambling.)

Each space was marked with an outcome that either helped or hindered the player. Landing on “honesty” or “temperance” was clearly preferable to the sins of the “drunkard” or “audacity.” The goal was to arrive at the heavenly mansion of virtue, having made good life choices. The game hung on so tenaciously in players’ memories that Parker Brothers reissued it as a “retro” sort of offering in 1894.

The increasing popularity of board games in the nineteenth century wasn’t only a matter of bringing up children properly. A good game fit well with Victorian-era parlor culture and was inherently social. The commercial viability, spread, and popularity of games were also aided by advances in chromolithography, printing, and literacy.

More to Explore

Gamification, Then and Now

The most famous modern brands in gaming emerged in the nineteenth century. Milton Bradley, originally trained as a draftsman and lithograph printer, commercialized the Checkered Game of Life in the 1860s. As with The Mansion of Happiness and in line with Bradley’s Puritanical faith, players navigated a path teetering between prosperity and ruin based on the spinner’s whims. The game board was scattered with evocative illustrations. Some spaces warned of the perils of immoral behavior; a player fell behind on squares like Poverty, Ruin, or the one marked by a child in a dunce’s cap under block letters shouting: “DISGRACE.” Conversely, players were launched upwards on squares like Honesty, Ambition, Matrimony, and Government Contract. The goal was to reach Happy Old Age with as many points as you could hoover up along the way. If you landed on the grim “suicide” space, the original rules mandated ejection from the game, “For how can any person continue to travel toward Happy Old Age after committing suicide?”

The goal in Mansion was to arrive at ease and moral satisfaction, but Bradley added a new layer: points. If you made it to Happy Old Age but hadn’t put enough in your purse along the way, you could still lose. “Always,” noted the rules, “strive to advance.” Bradley sold out an initial run of 45,000 copies handily in the game’s first year.

George Parker, of Parker Brothers fame, also emerged during this era, founding his game company in 1883. (He, like Bradley and Abbott, was from Massachusetts, which is apparently America’s most fertile historic gaming territory.) Unlike Bradley, Parker was eager to diversify his titles in the name of entertainment; his “twelve principles” of game play were more along the lines of good sportsmanship or management theory than sacred teaching.

(As a side note, Baltimore’s Charles Kennard hit on a spiritualist “talking board” craze in the mid-1880s and commercialized what would become Ouija, which you can keep because I will not touch one.)

Weekly Newsletter

These games were popular and enduring, because they were fun and because schools and public libraries embraced the idea of new paths into childhood learning. Librarians and psychologists suspected that toys and visual learning tools like games, puzzles, stereoscopes, lantern slides, and maps would invite children into spaces where they’d also fall in with traditional book learning, writes library and information science scholar Jennifer Burek Pierce. (This is to say nothing of the very unfortunately named “Sliced Objects” series.) Though famous for games, Milton Bradley also produced kindergarten visual lesson tools, zoetropes, and the “Historiscope,” a toy panorama showing more than two dozen colorful scenes from American history on rolled paper.

Some of the nineteenth century’s most popular board games are still available today. You can still play The Game of Life, to be sure. Games have continued to reflect their era’s joys and concerns: where The Game of Life worried about industrialization and morality, Monopoly was released amidst the Depression (and came from source material used by Elizabeth Magie to develop The Landlord’s Game, which raised moral questions about the ownership of private property). Parker Brothers released War in Cuba in 1897 so people could play the eventual Spanish-American War at home. Candy Land was developed against the backdrop of 1940s polio wards.

And some gaming scholars have argued that games like Bradley’s may have been influential on the later development of “social experiment” games like SimCity. Educators and scholars ask some of the same questions today about digital gaming and education as librarians did in the Gilded Age.