The Hidden Aesthetics of Early Astrophotography

Behind the transformative star photographs of the 1880s lay a complex collaboration between astronomers and engravers.

The Radioactive Reindeer Problem

Cold War nuclear testing left troubling levels of Cesium-137 in caribou, prompting years of research into Arctic fallout and its risks to human health.

Explaining the Tides Before Newton

Astronomical explanations for tides, usually credited to Isaac Newton, can be traced to thinkers like Strabo and Pliny in the Classical era.

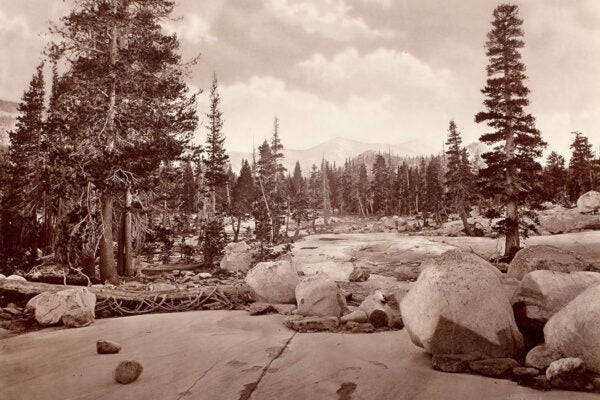

Living Laboratories: Science and the National Parks

National parks in the US are filled with glaciers and volcanoes, which isn't an accident, as the parks developed alongside the sciences of glaciology and volcanology.

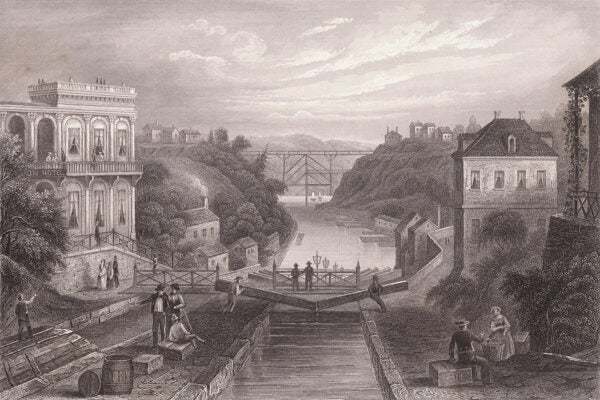

The Erie Canal at 200

Finished in October 1825, the Erie Canal connected increasingly specialized regions, altering the economic landscape of the northeast United States.

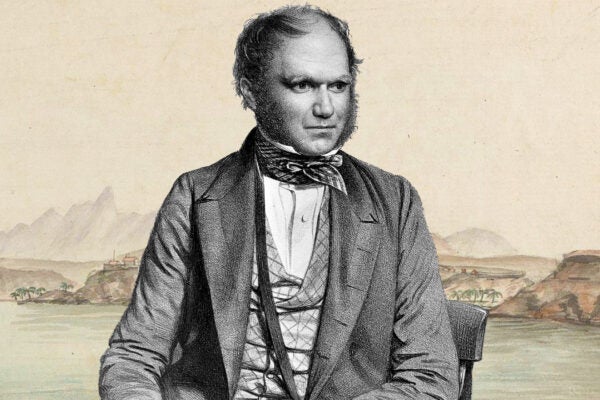

“Mad About Geology”: Charles Darwin’s Origin Story

At university and in the field, Darwin trained his scientific thinking as would a geologist, seeking causal explanations for observed natural phenomena.

A Practical Machine: The Wright Brothers in Dayton

Orville and Wilbur Wright wanted to create a practical machine—not a novelty or a gimmick—and they accomplished that at Ohio’s Huffman Prairie on October 5, 1905.

The Bee Dance Debate

Can insects communicate? In the middle of the twentieth century, scientists disagreed on whether bees could possess a “language” expressed through motion.

Arthur C. Clarke’s Scuba Adventures and Ocean Frontiers

Clarke’s interest in oceanic exploration in the 1950s was, like his undersea fiction, often neglected by an audience focused on the race for outer space.

Underground Conquest: Cave Exploration and Nationalism

As cave exploration became more popular and speleology developed as an academic discipline, cave explorers were drawn into a problematic European nationalism.

Fifty Years of Fractals

A half century ago ago, Benoit Mandelbrot coined the word "fractal" and pioneered a new type of geometry.

Convincing Peasants to Fly in the Soviet Union

With air-minded films, poems, and demonstrations, Soviet leaders sought to lift peasants out of their “backward” lives and into the world of the modern proletariat.

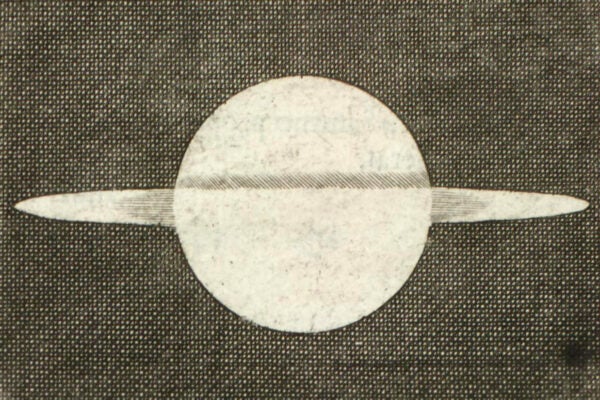

Christiaan Huygens and the Scientific Secrets of Saturn

Seventeenth-century science was so competitive that Christiaan Huygens used a cipher to conceal his Saturn observations when sharing them with interlocutors.

Phantoscopes, Radiovision, and the Dawn of TV

After creating a projector called the Phantoscope in 1895, C. Francis Jenkins successfully tackled the problem of transmitting motion pictures through radio.

Talking with Machines: Computer Programming as Language

The proliferation of different types of computing machines in the 1950s enabled—or perhaps forced—the creation of programming languages.

Science in War, Science in Peace: The Origins of the NSF

The 1950 establishment of a federal agency devoted to space, physics, and more belied a cross-party consensus that such disciplines were vital to national interest.

Electric Fish and the First Battery

Allesandro Volta invented the voltaic pile, the earliest electric battery, in part because of his investigations into the torpedo, an electric ray fish.

Was Carl Linnaeus Bad at Drawing?

Linnaeus has often been thought of as a poor artist, but visualization was a core element of his analytical tool set.

Robert FitzRoy and the Laws of Storms

When FitzRoy distributed barometers to local fishing communities, he empowered individual sailors to use their own judgment about the weather forecast.

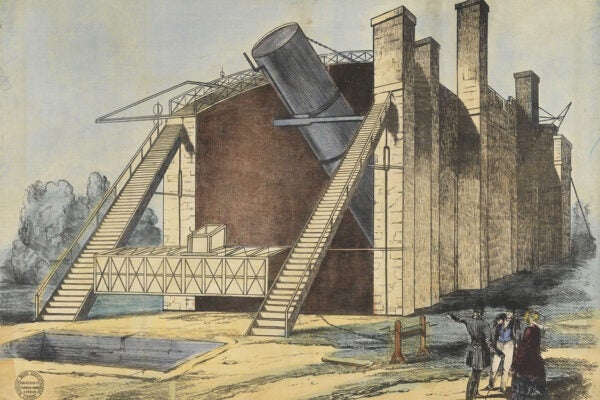

Leviathan Resurrected: Illustration and Astronomy

In the 1840s, the Leviathan of Parsonstown, built by William Parsons, third Earl of Rosse, became the largest telescope in the world.

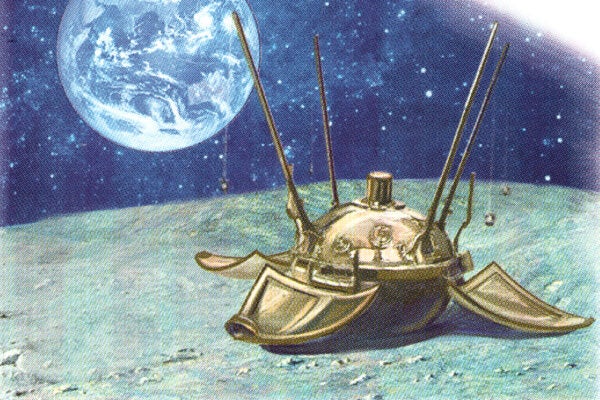

The First Lunar Lander and the Great Moon Dust Debate

In 1966, the Soviet Union’s Luna 9 became the first spacecraft to soft-land on the Moon, helping to resolve questions about the nature of the lunar surface.

The Origins of the “Dinosaur Renaissance”

John Ostrom’s ideas were part of the so-called Dinosaur Renaissance, a paradigm shift that posited dinosaurs as the warm-blooded ancestors of birds.

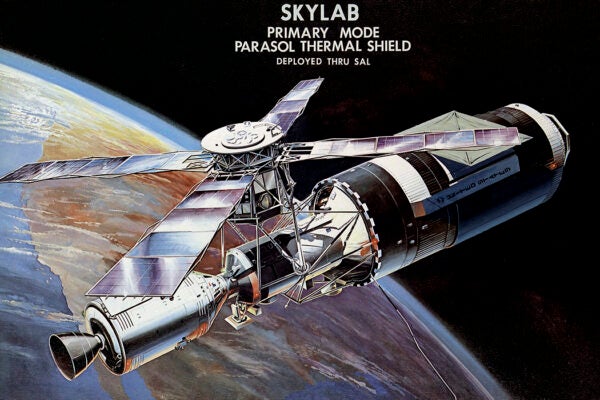

Skylab, Sealab, and the Psychology of the Extreme

During the Cold War, small groups of Americans lived together in space and at the bottom of the sea, offering psychologists a unique study opportunity.

The Open Polar Sea: Myth and Science at the North Pole

The idea of an open polar sea haunted the imaginations of European explorers and scientists alike in the nineteenth century.

How Interwar Britain Saved Their Dogs

Canine distemper became a major threat in Great Britain after World War I. Saving the nation’s dogs depended on an imperfect collaboration.