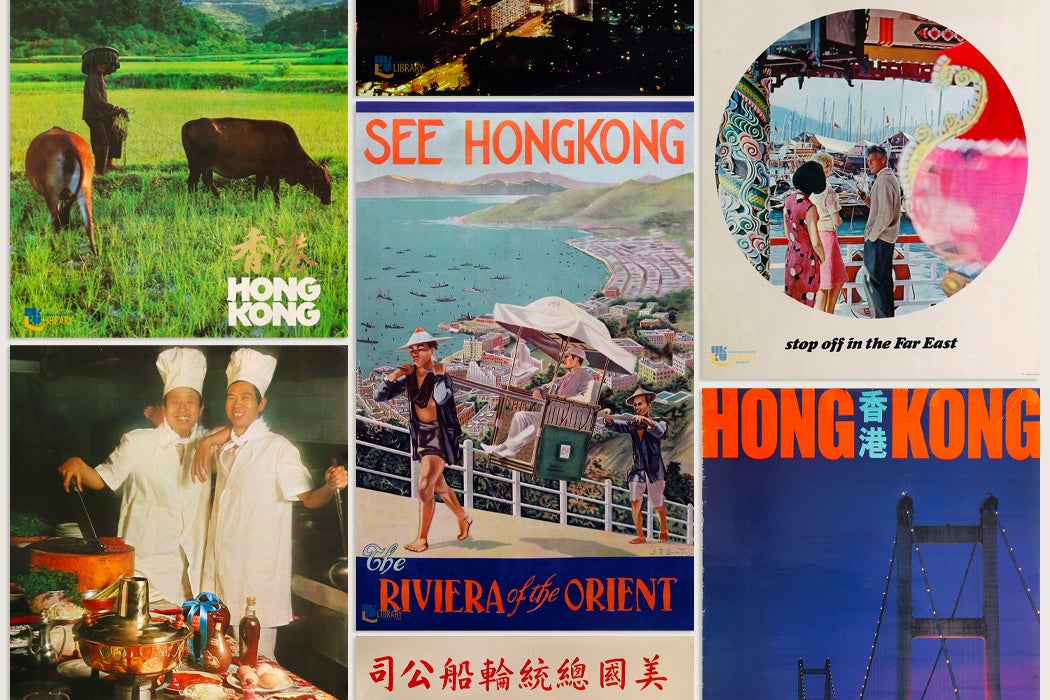

Located on the coast of southern China, the territory of Hong Kong spent much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a British colony, caught, in a quirk of history, between two worlds. Colorfully showcasing this identity, a collection of travel posters held by Hong Kong Baptist University offers insight into the city’s unique place in the global imagination over the decades.

Many of the collection’s more than 100 posters hark back to the golden age of international aviation, featuring now-defunct names like BOAC and Pan Am. History and tradition feature prominently in their rhetoric but so do themes of modernity and cosmopolitanism. After all, the cliché of Hong Kong as a place where “East meets West” is, according to D. J. Huppatz, “a common stereotype that continues to be used in contemporary criticism, journalism, and tourism promotion.”

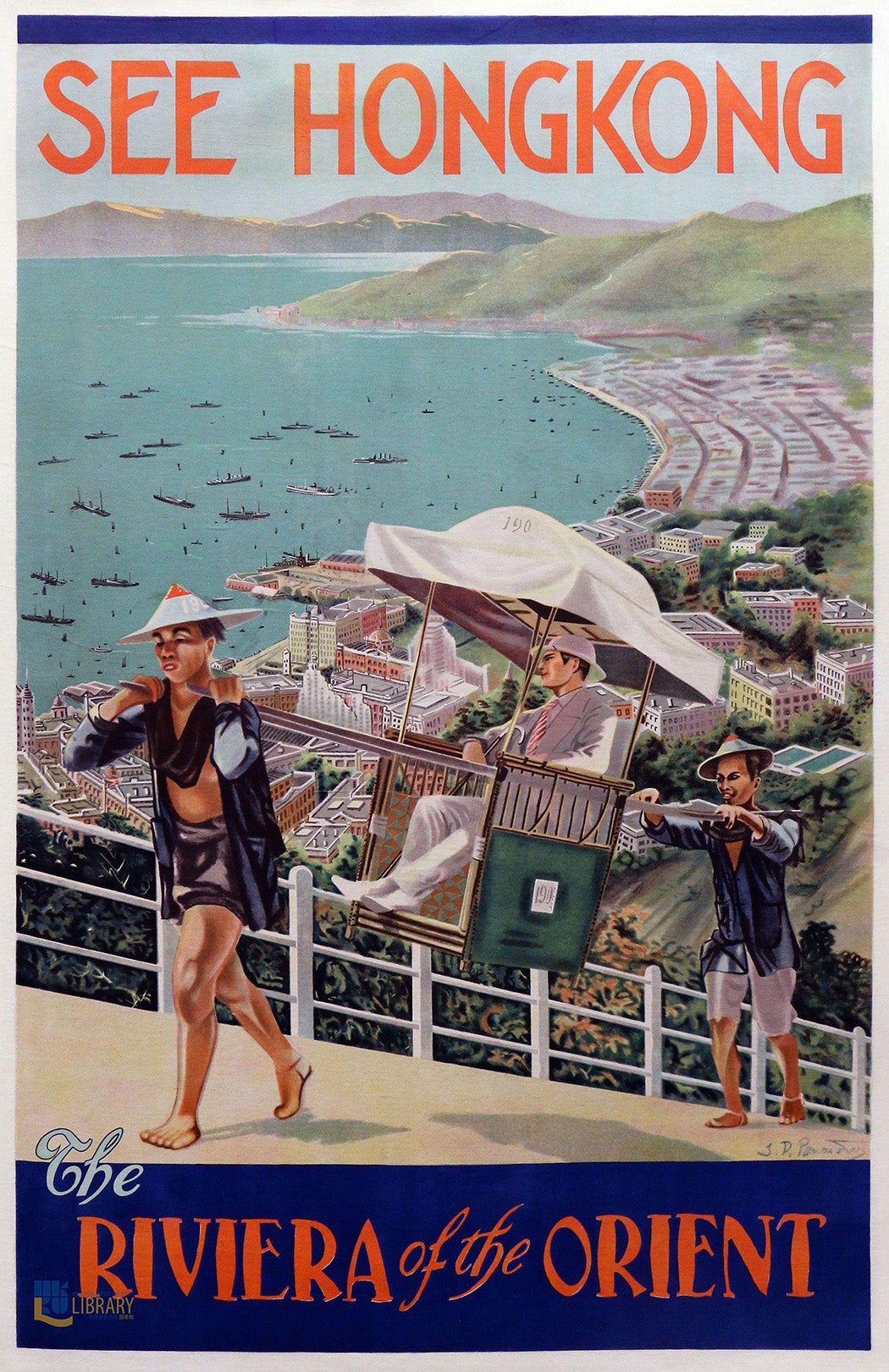

One of the oldest items in the collection dates to 1935, the year that the Hong Kong Travel Association (HKTA) was established. The poster is signed by S. D. Panaiotaky, who also designed several other travel flyers promoting Hong Kong as a destination.

Calling attention to the warm color palette and view of the sun-drenched harbor, the poster bills Hong Kong as “The Riviera of the Orient,” a tagline that also served as the title of a guidebook published by the HKTA around the same time.

The atmosphere of leisure and ease is accentuated by the picture’s focal point: a white tourist in a summer suit, journeying uphill in a sedan carried by two barefoot Chinese men. Bruce A. Chan, who grew up in mid-century Hong Kong, recalls that the city’s Peak and Mid-levels districts were European-only residential areas before World War II, as “[c]oncern for hygiene and comfort drove the colonials to live at the higher altitudes of Victoria Peak where they could escape the noise, congestion and poor sanitation of downtown.”

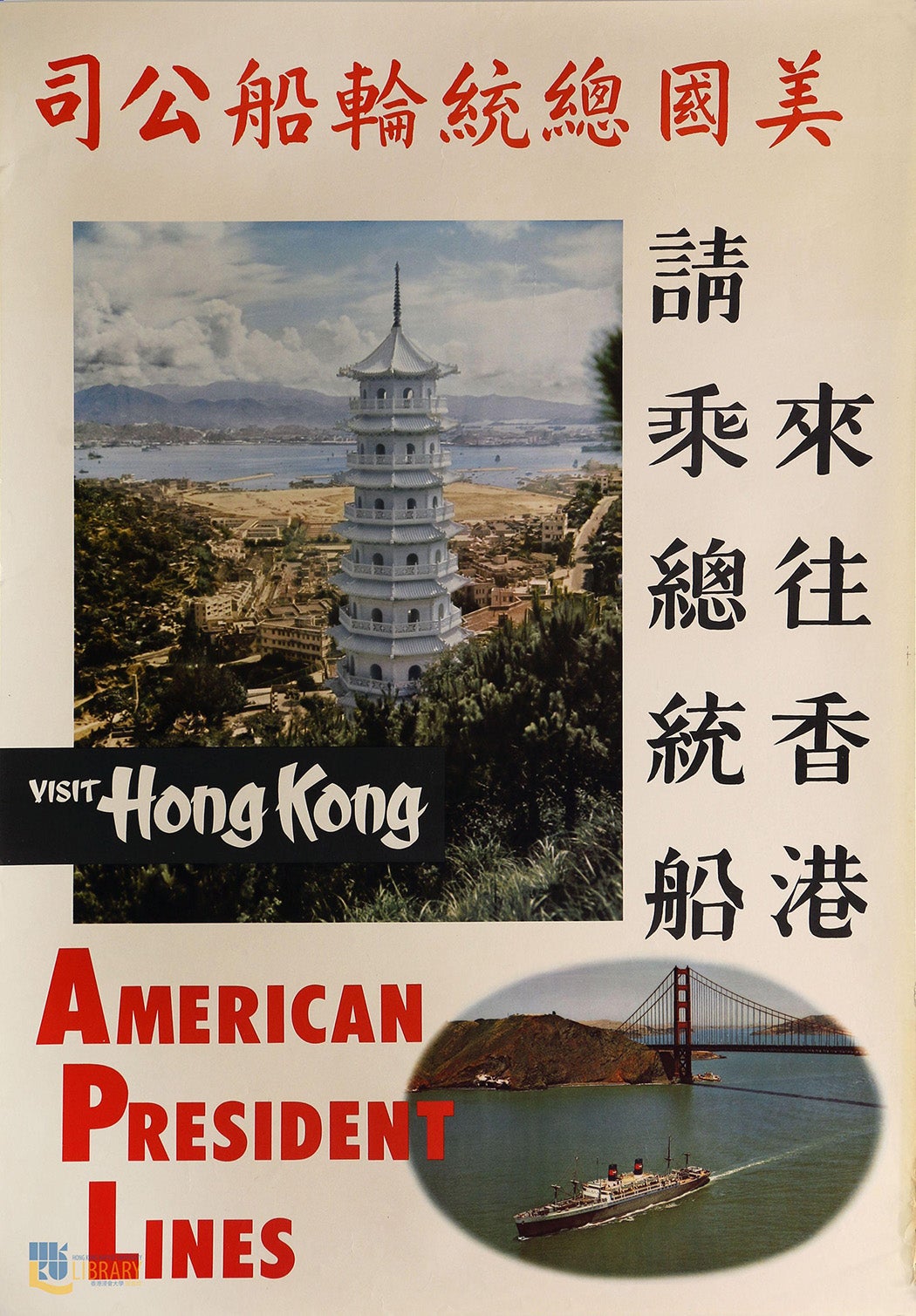

An American President Lines (APL) ad from the late 1950s has an “[u]nusual and forward-looking design” for its bilingual exhortation to “Visit Hong Kong.” Beneath the prominent photograph of the Tiger Balm Gardens pagoda in Hong Kong, the poster shows a smaller picture of the SS President Cleveland passenger ship sailing under the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco—the reverse voyage on a transpacific route that countless Chinese migrants had long taken to California’s “Gold Mountain.” From the 1850s, Hong Kong was “the gateway to the Pacific as well as a pivot in the Cantonese diaspora,” writes Elizabeth Sinn.

One hundred years later, ocean liners—a mode of transport that Tricia Cusack argues helped to popularize the reach of the British Empire for upper-class travelers—would be superseded by the convenience of commercial air travel. Still, Hong Kong remains a key node in global shipping networks. Writes Sinn, “When the Pacific Ocean turned into a highway for Chinese seeking Gold Mountain, it marked a new era for the history of South China, California, and the ocean itself.”

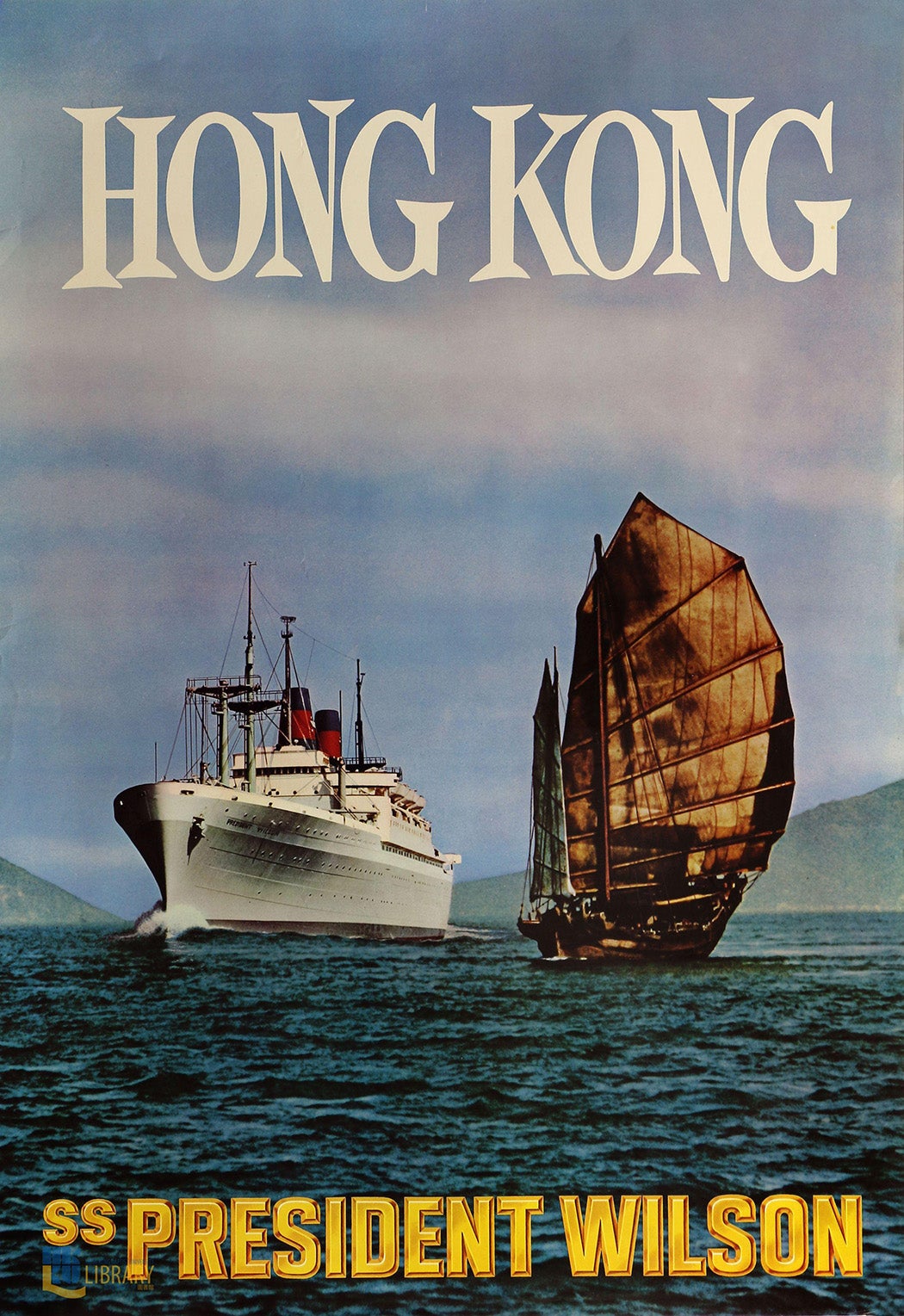

Besides the President Cleveland, another ship in the APL’s fleet was the SS President Wilson, which operated from 1948 to 1973 on the shipping line’s transpacific service. As the collection’s curator notes, a poster from the early 1960s “allows APL to show their ship steaming into Hong Kong past a Chinese sailing junk, juxtaposing not just East and West but also modernity and tradition.

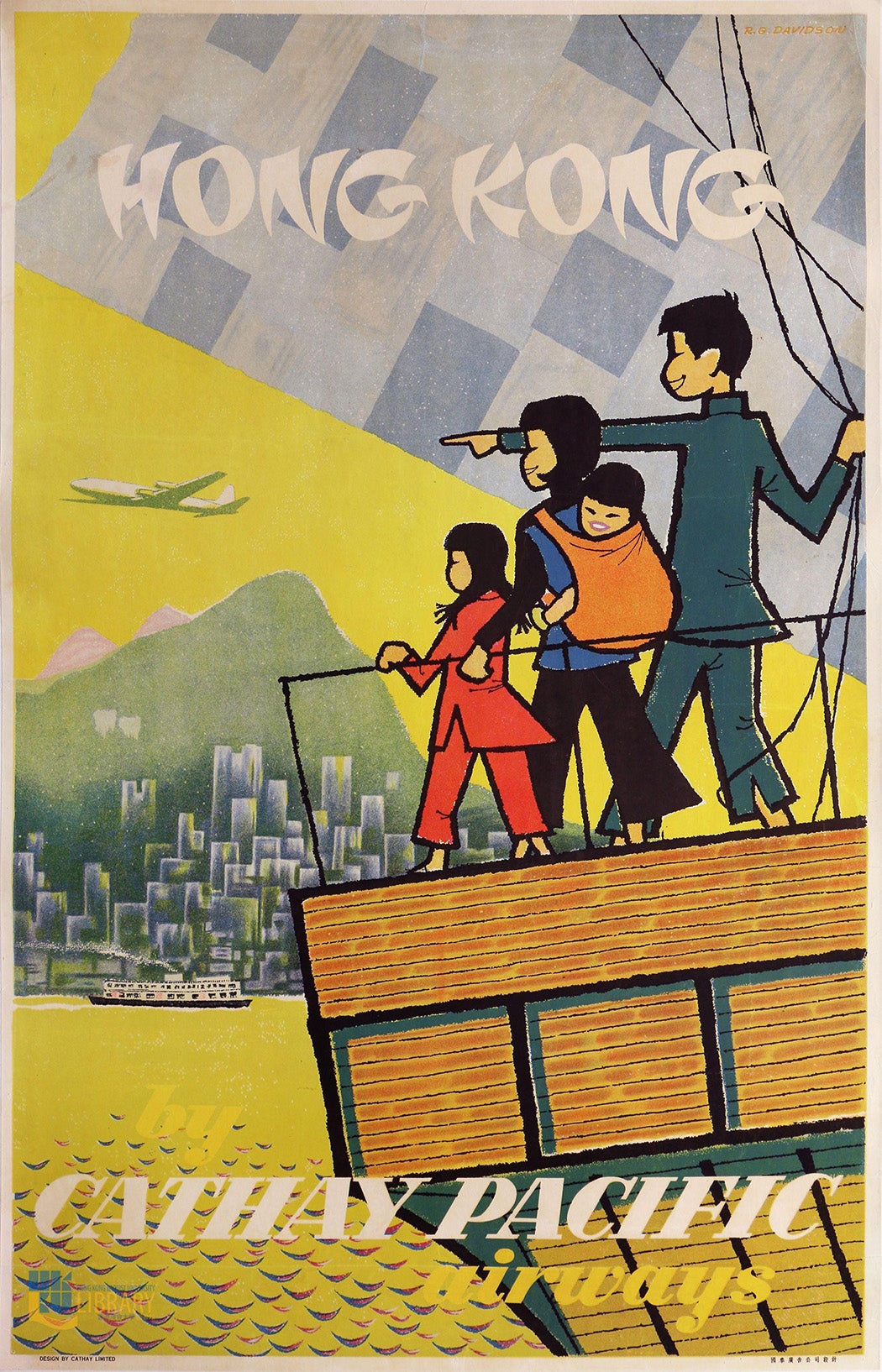

From ships to jets, Hong Kong’s story as an aviation hub would be incomplete without Cathay Pacific Airways. The company’s name evokes a centuries-old Western image of China and, in one early poster advertising travel to Hong Kong, Cathay Pacific offers a scene that shows a “traditional” Chinese family aboard a sailing junk staring in awe at the modern high-rise city and jet plane in the distance.

Commercial flight was historically a profession that opened doors to the world for women workers, especially as it was associated with globe-trotting glitz. However, female flight attendants also faced considerable discrimination, as they were expected to conform to stereotypes around race and gender. Stewardesses on Japan Airlines “had to simultaneously represent modernity and exoticism when they flew from the East to the West” in the 1950s, Yoshiko Nakano argues.

The experience of the Cathay Pacific flight attendants featured on a 1959 poster may have been similar. Even though Asian employees clearly appear in the line-up of uniformed Cathay Pacific crew on the tarmac, the copy touts the carrier as “a British airline with British pilots.”

The Hong Kong Tourist Association, a successor to the pre-war Hong Kong Travel Association, was launched in 1957 as the brainchild of executive director H. F. Stanley, a Briton who took an interest in promoting a distinctive identity for the British colony.

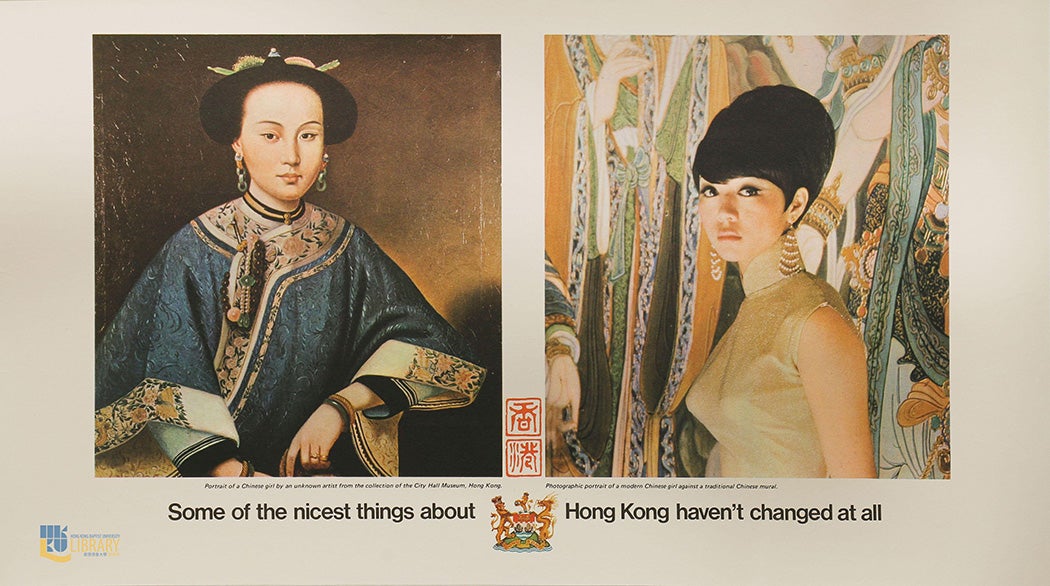

An early poster from the new version of the HKTA illustrates how colonial admen stressed continuity with a longer Chinese cultural tradition as a selling point for visitors to Hong Kong. The poster juxtaposes the antique painting of an anonymous “Chinese girl” with the photograph of what the caption calls “a modern Chinese girl against a traditional Chinese mural.” Images of traditional Chinese garments were historically used to represent China as “as an ancient but stagnant country,” writes Heather Chan in her analysis of the evolving portrayals of Chinese fashion in Vogue magazine from the 1890s to 1940s. At the same time, Anne Anlin Cheng theorizes that Western culture turns the figure of the “yellow woman” into “an inherently aesthetic object,” in a phenomenon she dubs ornamentalism.

Chinese women’s bodies are the focus of the poster’s marketing, yet its tagline, “Some of the nicest things about Hong Kong haven’t changed at all,” is stamped with the British crest. In a Japan Air Lines poster from the same period, eagle-eyed viewers will similarly spot the flag of the British merchant navy in the background.

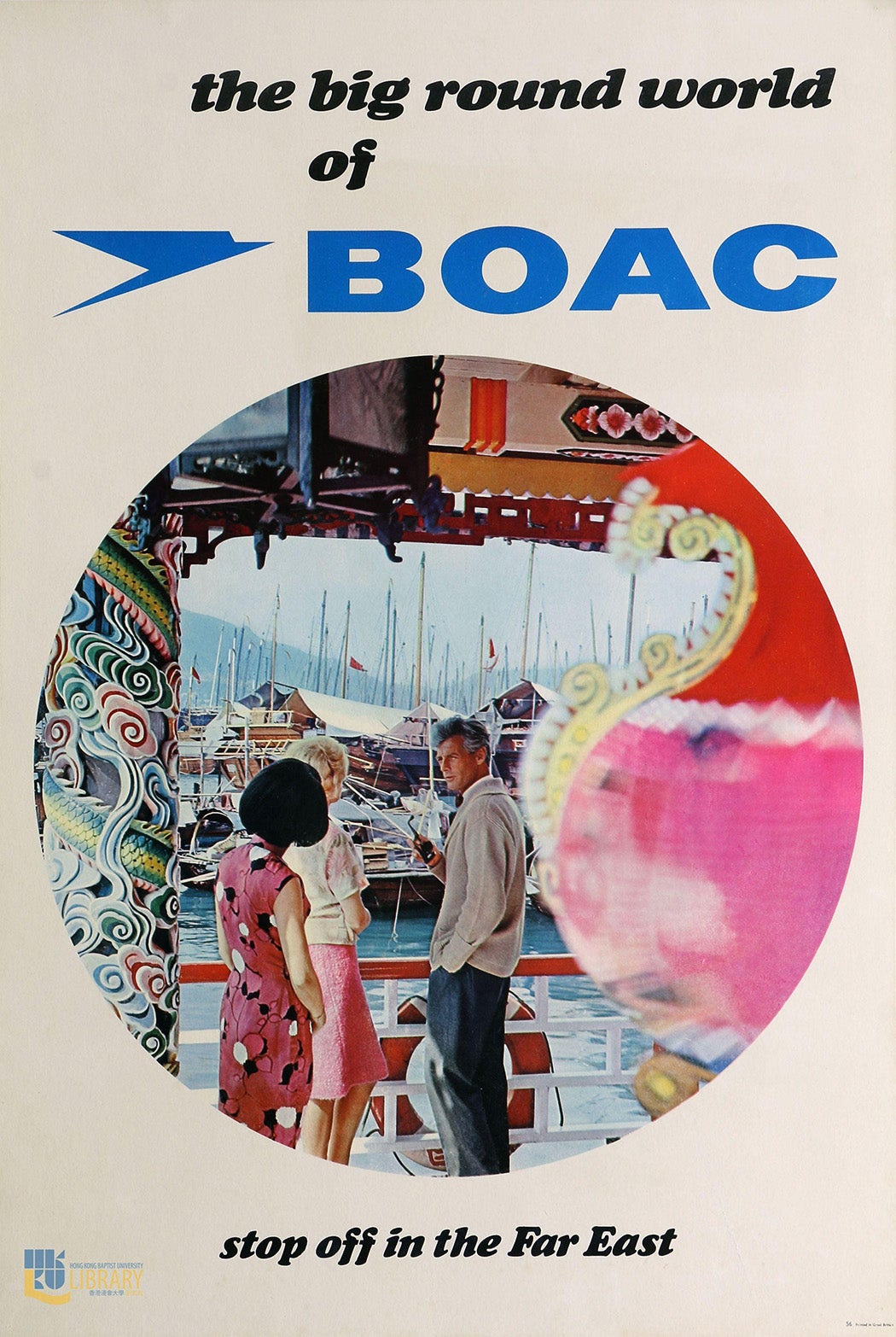

The British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC, advertised its connections to “the big round world” with an exhortation for travelers to “stop off in the Far East” around 1970. A c. 1970 promotional poster advertising BOAC’s services positions Hong Kong as a synecdoche for the Far East as a whole, depicting a white tourist couple on the promenade of a floating restaurant in Aberdeen harbor, a popular destination at the time.

But one of the tourists in the poster isn’t looking at the boats on the water: his gaze is directed at a cheongsam-clad local woman—maybe a waitress?—shown only from behind. The poster references the 1960 film The World of Suzie Wong, which, featuring a Chinese sex worker as a main character, popularized the qipao as “the Suzie Wong dress” in the West. (The character of Suzie Wong also etched a notorious and unwanted link between “any yellow(-looking/sounding/tasting/smelling) women” and “the under-world of porn industry, mail bride industry, global sex trafficking, etc.,” Kyoo Lee argues.)

Today, the waterfront settlement of Aberdeen “houses Hong Kong’s largest and most important remaining marine community,” reports Victor Tsz Hin Leung. It’s crowded with houseboats, fishing vessels, roving vendors in sampans, and multi-story floating restaurants that drew tourists until the COVID-19 pandemic forced them to shutter.

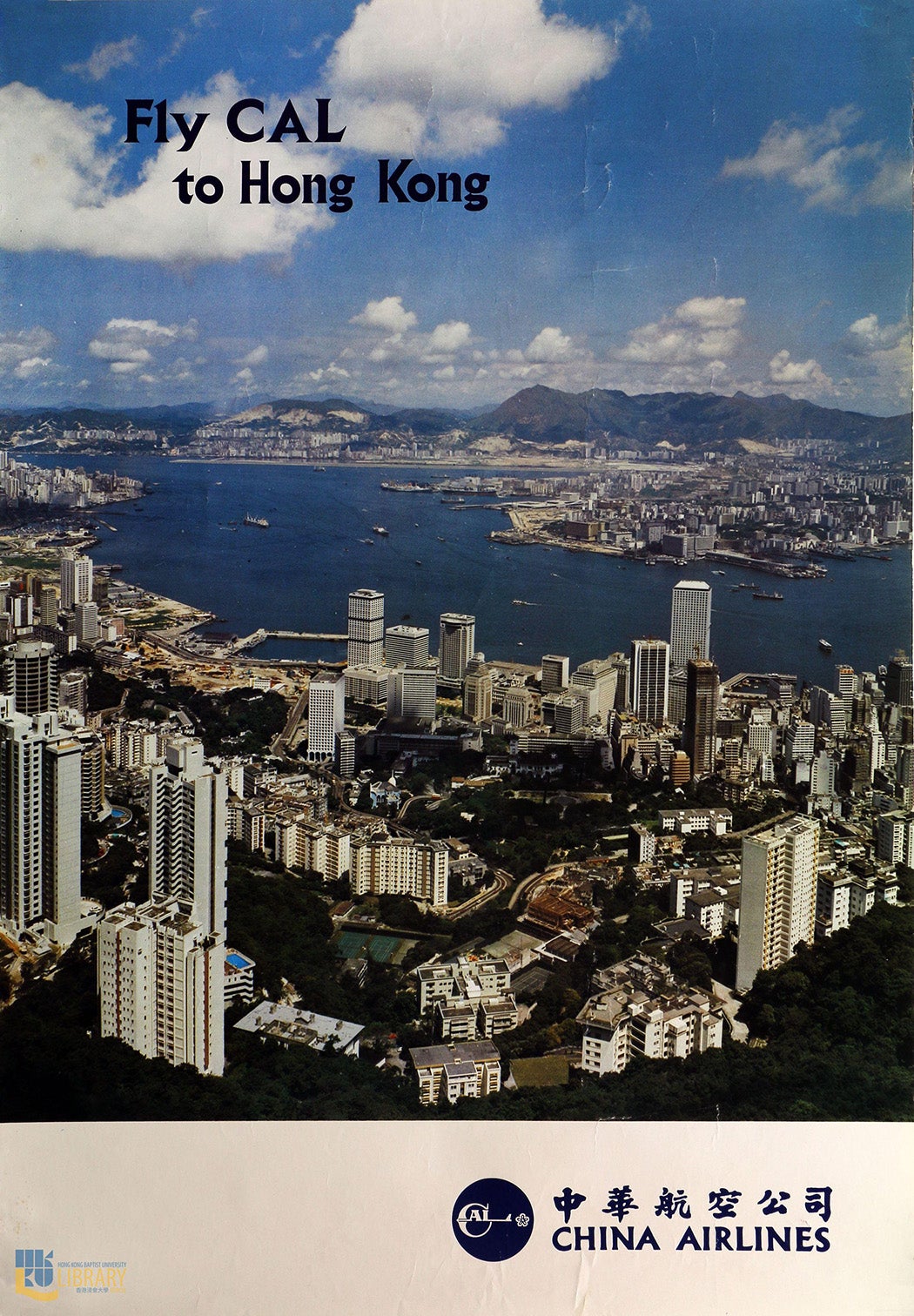

Dating to roughly 1977, the above poster by the Taiwanese China Airlines (CAL) encourages passengers to “Fly CAL to Hong Kong.” The carrier began flying into Hong Kong in the 1960s. The poster offers an aerial view of the destination, showing Hong Kong harbor and the New World Tower being constructed on Queen’s Road Central. However, the photo has been printed in reverse.

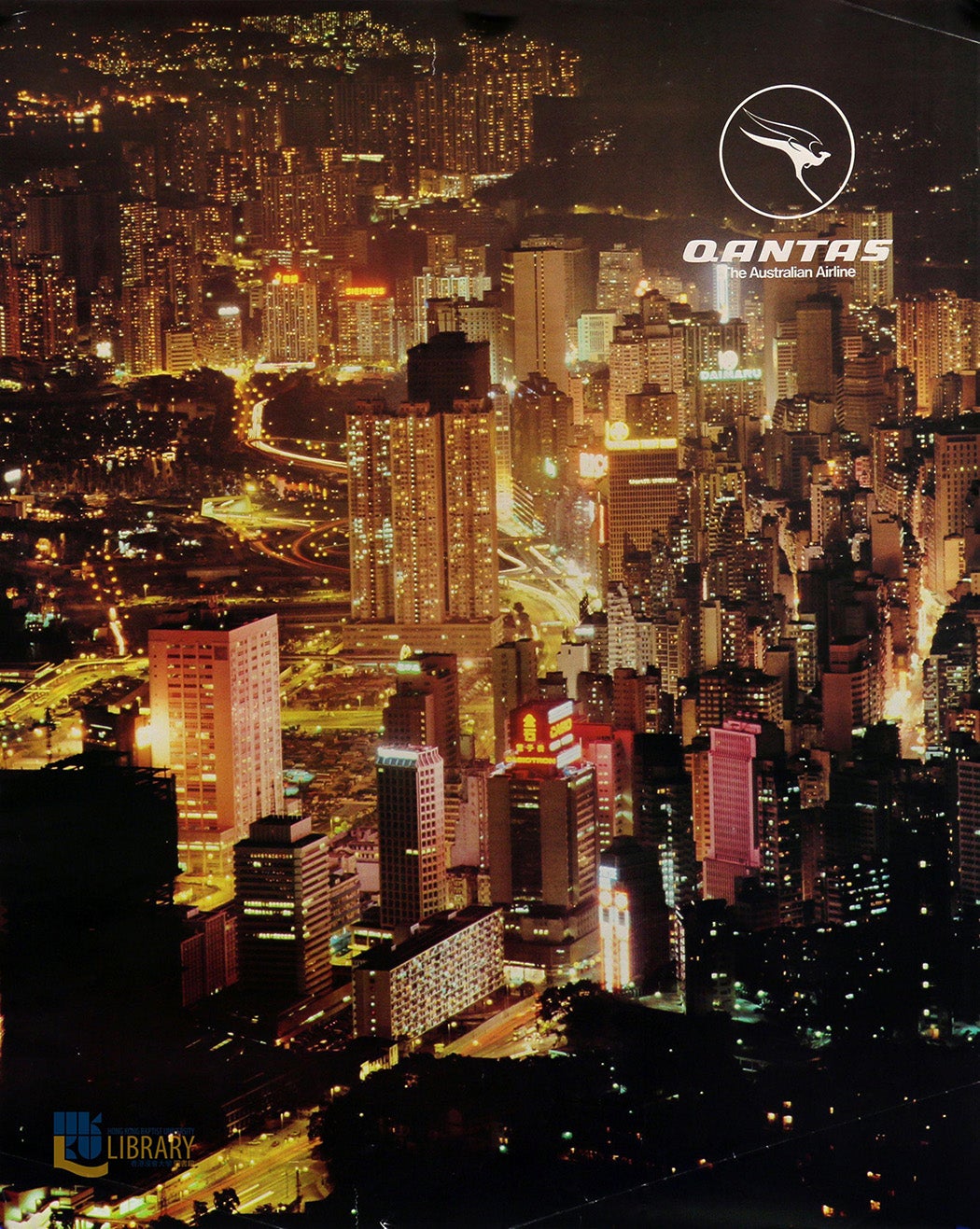

Showing the city’s high-rise buildings from a different angle, Hong Kong’s night-time skyline shines in a poster printed by the Australian flag carrier Qantas in the 1970s. As early as 1950, travel posters played up Hong Kong’s urban landscape—what Tsung-yi Huang calls the “much-publicized image of the dazzling ‘Pearl of the Orient,’ a capital showcase displaying nothing but spectacle and fantasy” at odds with the city’s reality.

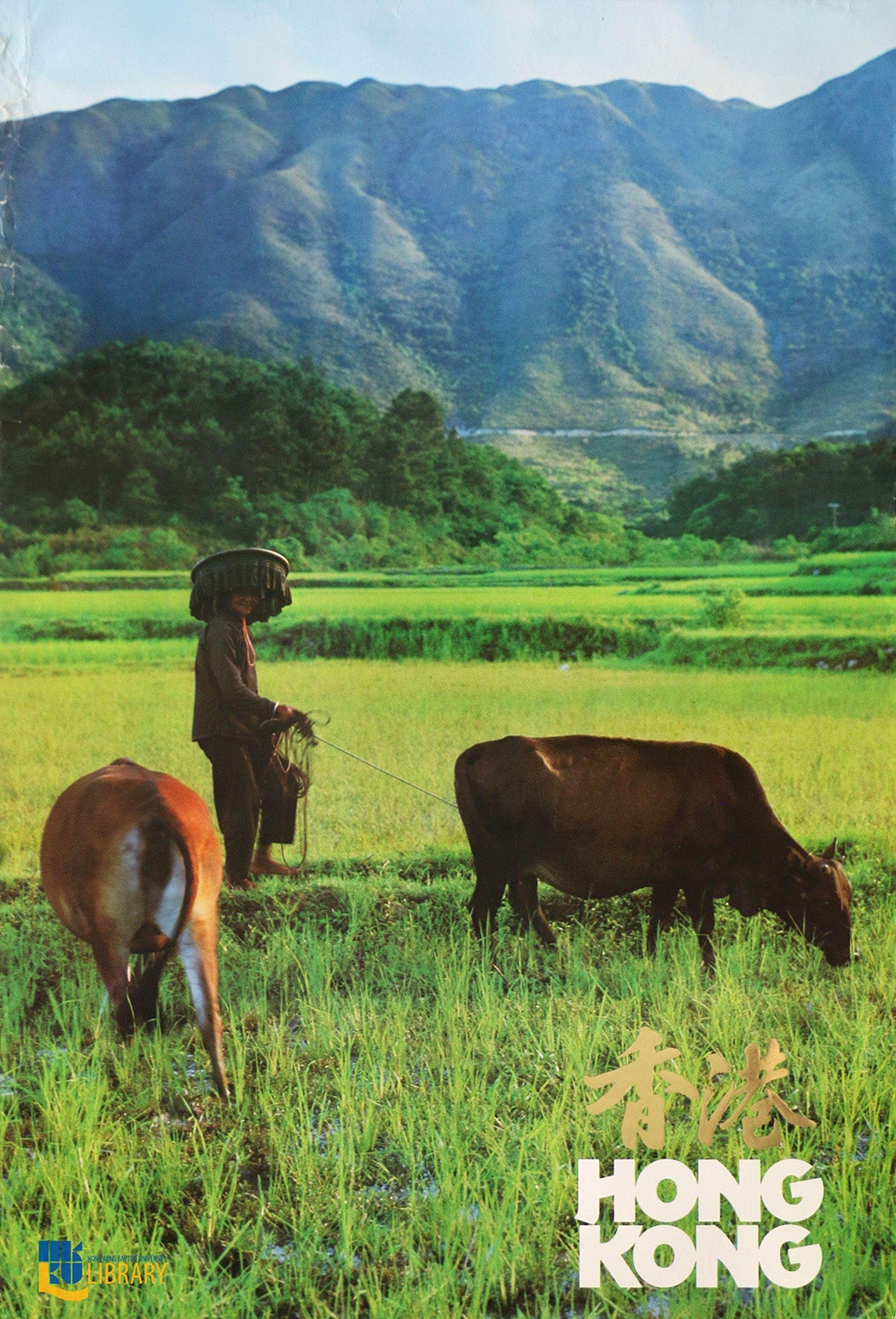

Still, there’s much more to Hong Kong than the glamour of its modern skyscrapers. Published by the Hong Kong Tourist Association, a c. 1980 poster shows an old woman tending a pair of cows amid lush greenery, with rolling hills in the background. In fact, the British possession of Hong Kong extended beyond Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon peninsula. Much of its land area lay in the New Territories, which were important to the colonial government because of the potential of their agricultural and mineral resources.

The HKTA had long championed the tourism potential of the New Territories. Not long after it was set up in the 1960s, it commissioned a landscape painting that depicted the view of Hong Kong and Kowloon from the agricultural hinterland.

“Dotted with villages, peopled by villagers, worked by buffaloes, decorated with paddy-fields and duck farms, the New Territories boasts pagodas like the Temple of 10,000 Buddhas, overlooking Shatin Valley,” the association’s advertisement enthused.

In 1974, the organization further offered funding for academics to research historical Chinese buildings in the New Territories, resulting in a publication on rural architecture.

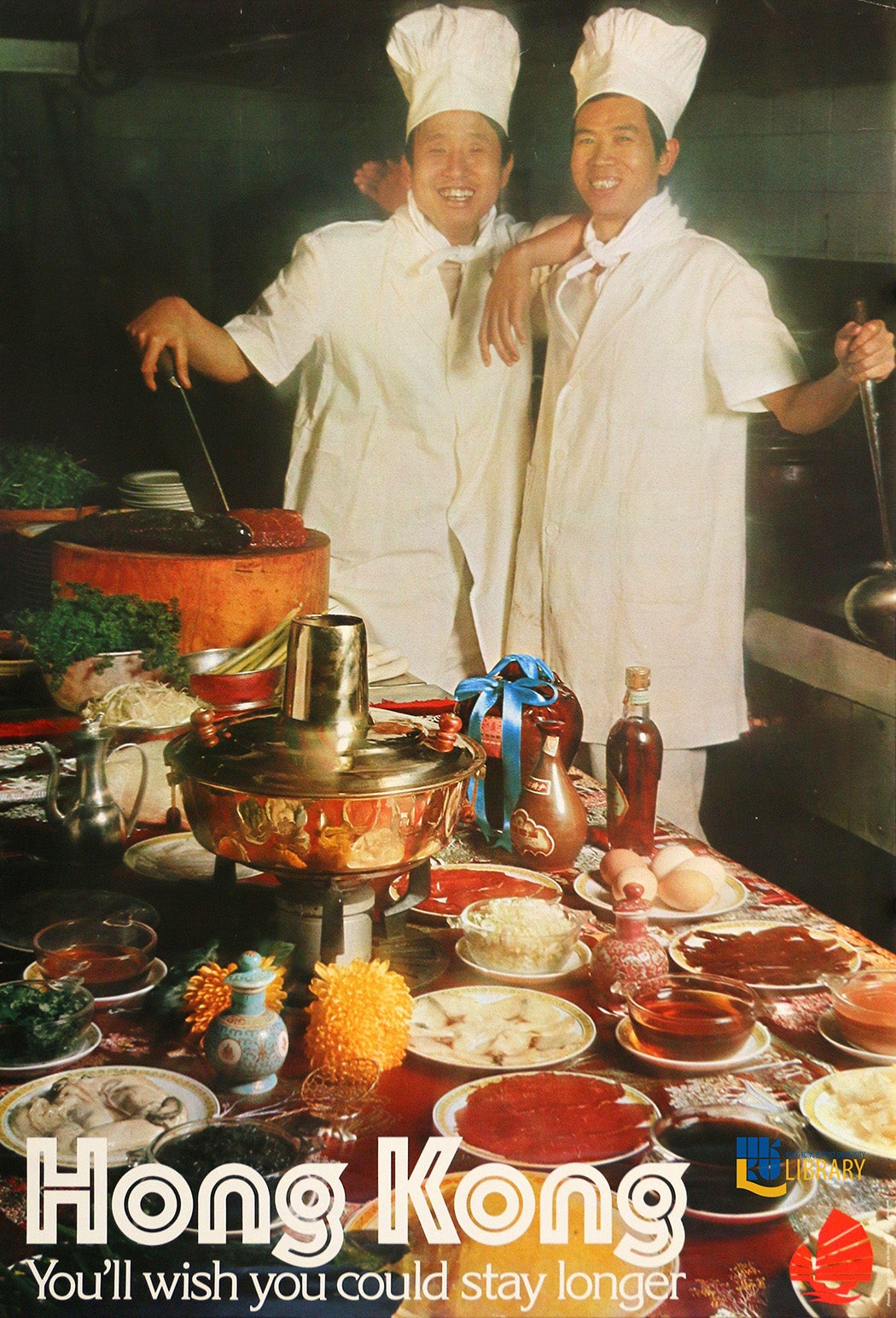

Besides architecture, the HKTA also highlighted other aspects of culture, as in a photograph of two chefs with Chinese dishes laid out before them. In 1980, when the poster was published, Hongkongers could see the writing on the wall for the British, with talks under way to return sovereignty to the People’s Republic of China. Despite their shared Cantonese cultural heritage, Hong Kong’s cuisine differed markedly from that of the neighboring Chinese province of Guangzhou.

“The two decades leading up to the 1997 Handover witnessed an intense and unprecedented interest in Hong Kong culture,” writes Daisy Sheung Yuen Ng. A “fear of the disappearance of Hong Kong’s way of life” under Chinese rule fueled a nostalgic frenzy for the romanticized trappings of “Old Hong Kong.”

Weekly Newsletter

“Besides the typical scenes of junks, and nightscapes, another popular image of Hong Kong in tour books is Cantonese dim sum,” Ng writes. “A glossy photograph of dim sum always figures prominently in the promotion pamphlets of the Hong Kong Tourist Association.”

Despite the change in government, Hong Kong was still portrayed as a vibrant, cosmopolitan trading hub after the handover of the territory. A Hong Kong Tourism Board poster from 1998 bills “Visionary Hong Kong” as both a bridge between East and West and “the pathway to the future.”

Even with the city’s major changes in the last century, tourism retains a significant role in the Hong Kong economy. The story told by the travel posters in this collection documents the historical growth and captures the shifting mood of a remarkable, truly global city.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.