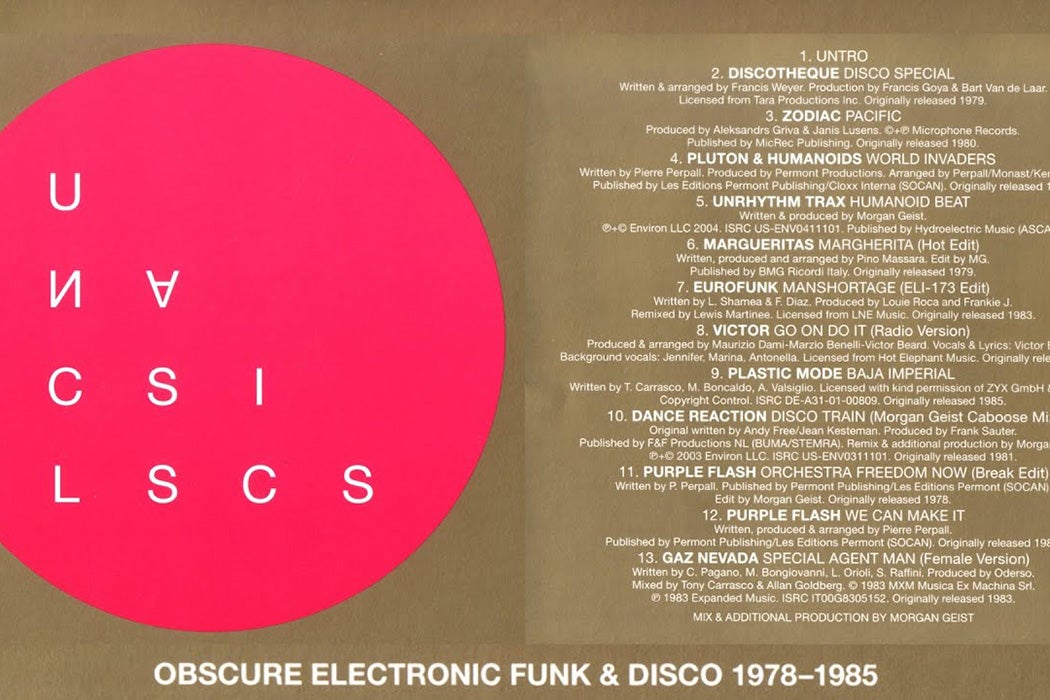

Since the turn of the millennium, Eurodisco—and its most eminent subgenre, known as Italo Disco—has undergone a steady revival, allowing it to shed its cheesy and kitschy veneer and make a case for its transcontinental appeal. For the uninitiated, Italo Disco, whose name was coined by the German discographer Bernhard Mikulski from ZYX, combines electronic drums, synths, vocoders, and melodic flourishes associated, to varying degrees, with Italy. One of the early revival examples is the 2004 compilation Unclassics: Obscure Electronic Funk and Disco, 1975–1985, released by Environ Records.

“Unclassics is one milestone within the significant rehabilitation of European and Italian disco that has unfolded over the last decade,” writes Will Straw in the journal Criticism. The compilation does, indeed, contain tracks from all across the continent.

And yet, the artist who takes up the most space on the compilation is from neither Italy nor Europe, but from the Canadian province of Quebec. Montreal-based producer and performer Pierre Perpall, a former soul singer appearing under the names Pluton and the Humanoids, Purple Flash, and the Purple Flash Orchestra is behind three of the tracks: “World Invaders,” “Freedom Now,” and “We Can Make It.”

“World Invaders,” released by Pluton and the Humanoids in 1981, is today the most cherished of Perpall’s dance tracks and has a markedly Italo Disco flavor. It embodies the formula that defines the genre: extravagant lushness that often went hand in hand with a cold, mechanical quality, and a theme of space exploration that also appeared in Eurodisco hits such as La Bionda’s “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” in Sheila’s “Spacer,” and Sarah Brightman’s “I Lost My Heart to a Starship Trooper.”

So, what’s the cultural and musical kinship between Euro (and Italo) Disco and Quebec? In the mid-1970s, Montreal functioned as a point of passage and reassembly for dance records circulating internationally.

“Montreal was a key point of transit for music that came from somewhere else,” writes Straw. “Stereotypically, Montreal has long been seen to mediate between the cultural influences of Paris and New York, Europe and North America.”

Additionally, Quebec labels and performers cultivated a deliberate vagueness about their identities, with the hope that record buyers and industry professionals might think that records produced in Canada were actually from somewhere else. There were a host of disco performers, Straw writes,

whose Quebec or Canadian origins were not widely known or suspected, including Claudja Barry, Suzy Q, Karen Silver, Gino Soccio, and Patsy Gallant. “Records by these performers often perpetuated the long-standing tendency of Canadian or Quebecois to hide (or, at the very least, downplay) their origins, to look as if they came from more credible centers of cultural authority.

The Croatian website Italo Disco Net notes that many of the records perceived as European in the late 1970s and early 1980s were actually from Canada (and mostly from Quebec). Additionally, the inclusion of a Quebec track (“Un Habit en la Bémol” by Roger Gravel and Flashback) on the 2006 Italo compilation Baia degli angeli 1977–1978: The Legendary Italian Discotheque of the 70s pushed the value of the original twelve-inch LP higher on the collector’s market, fueling a more general pillaging of Quebec record crates by international collectors of Italian-inflected disco.

More to Explore

The Year The Grammys Honored Disco

In places like Quebec or Italy, the character of disco music was influenced by its own entertainment cultures, resulting in, on one hand, local success and, on the other, what can be deemed as diminished integrity and exportability and, to more cosmopolitan ears, kitschiness.

“These local entertainment cultures included television programs that encouraged lip-synching and extravagant performance,” Straw writes, “and so kept disco tied to regional (and, from many perspectives, degraded) traditions of audiovisual variety entertainment.” Further adding to the lowbrow component, Straw credits Latin countries’ local tourist-leisure economies, “which, bringing together audiences of uncertain taste and composition, often encouraged music of broad appeal that might well appear to be pandering.”

Weekly Newsletter

Last but not least, this kinship also boiled down to the fact that Italians and Quebecois did share aesthetic sensibilities. Straw lists a penchant for florid exuberance in melodies, accompanied by an eroticization that exploited the “sexy” resonances of Romance languages.

“Indeed, it is easy to see the messy eclecticism of much Italian or Quebec disco as expressing hedonistic, Catholic, and anti-puritanical impulses stereotypically taken to define these places,” Straw states.