Path to Open Books on JSTOR

“In a refugee camp,” Iranian American author Dina Nayeri writes in her 2019 novelistic memoir, The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You, “stories are everything. Everyone has one, having just slipped out from the grip of a nightmare, [they] transported us out of our places of exile, to rich, vibrant lands and to home.”

According to Peter Sloane, a senior lecturer in English literature at the University of Buckingham and author of From Rupture to Refuge: The Coordinates of Contemporary Refugee Narratives (Liverpool University Press), this quote offers but one of many examples of how writing by refugees about the refugee experience helps those who’ve been displaced make sense of their disrupted lives and regain a sense of agency and belonging.

The extratextual functions of refugee writing are numerous. On one level, Sloane explains, they’re a means of personal and communal rehabilitation—what Atia Abawi, a journalist born to parents who fled the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan during the 1980s and author of the 2018 novel A Land of Permanent Goodbyes, calls the act of sharing and lightening “the burden of your past.” On another level, refugee writing challenges narratives about immigration and asylum promulgated by Western mainstream media and political discourse that shun individual stories in favor of numbers and statistics, ignore or downplay the colonial causes of mass displacement across the Global South, and frequently (as well as incorrectly) represent refugees as terrorists and economic opportunists.

At a time when more than 100 million displaced people are denied basic human rights, writers like Nayeri, Abawi, and Christy Lefteri, Sloane asserts—quoting the protagonist of Lefteri’s The Beekeeper of Aleppo (2019)—remind themselves and their readers that refugees aren’t the “worst people in the world,” as populist demagogues would have you believe. Rather, they are people in the “worst place in the world.”

Although Sloane is well-versed in the historical, political, and economic dimensions of refugee studies—regularly referring to Hannah Arendt, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Thomas Nail, and other influential philosophers of person and statehood—From Rupture to Refuge is not, ultimately, a work of social science. Included in JSTOR’s Path to Open program, which supports the open access of university press materials, this book is an exercise in literary criticism, aimed at a rich, relevant, and hugely understudied type of writing—at its tropes, inspirations, and capacity to “understand and then to start to reverse the displacement to which [its authors] have been subject.” With the publisher’s permission, we are making available “Writing Escape,” the third chapter of Sloane’s examination for a period of three months.

The following interview has been edited for clarity.

Tim Brinkhof: What motivated you to undertake this study?

Peter Sloane: It evolved from an aborted book on literature and altruism, which was supposed to include a chapter on refugees. I became so intrigued by the texts I was reading that I ironically abandoned the altruism and focused entirely on refugee writing. I also became increasingly conscious of the ways in which refugees were reduced to categories, or a single category which paradoxically but conveniently connoted both weakness/desperation and threat. It seemed important to move beyond, or away from, the mainstream to explore writing that was more politically attuned than my previous subjects. More than anything, though, it was the awful death of Alan Kurdi [the boy from Syria whose body, washed-up on the shores of Turkey after he drowned in the Mediterranean, made international news when photographed in 2015]. The horror of that avoidable loss that stuck with me and kept coming back.

In the introduction to From Rupture to Refuge, you quote literary and cultural theorist Leela Gandhi asking how scholars can “avoid the inevitable risk” of presenting themselves “as an authoritative representative of subaltern consciousness.” You then agree that “intellectual exploitation is always a peril when attempting, however sensitively, to confront experiences of the suffering of distant and distinct others.” How did you navigate that challenge while working on the book?

By paying attention to the voices. I was interested in what they had to say, in their own records, sensations, representations. Foremost, I was attempting to think through a form of writing in the English language that was novel but emerging in prominent ways. We’d had The Kite Runner, The Beekeeper of Aleppo, Nayeri’s The Ungrateful Refugee, and each of these had pushed both refugee writing and experience into the mainstream. It seemed legitimate and important to recognize refugee writing as writing, as art, as part of a tradition. I have now moved on to other projects, including a forthcoming collection of essays on global refugee arts edited by myself and Dr. Katie Brown of Exeter. For me, the refugee life is something I can pick up and leave behind at will, and there remains something overtly problematic about that—a manifestation of my privilege.

You argue that refugee writing challenges generalizations promulgated by Western media and political discourse. At the same time, the purpose of your book is to identify common tropes and patterns within this type of literary output. Did you experience any tension or difficulty in trying to group together narratives that were written in part to re-individualize stories about refugees and the refugee experience?

Each text, whether fiction or memoir, uses the recollection of a lost land as a backdrop, a foil against which individual journeys emerged in contrast. Since I studied refugees in their own words, it seemed to me less damaging to draw out the ways in which their recollections intersected. Still, I had to be vigilant to not clump them together, not to elude the idiosyncrasies which differentiated their experiences in important ways, and not slip into the trap of dealing with categories instead of people.

More to Explore

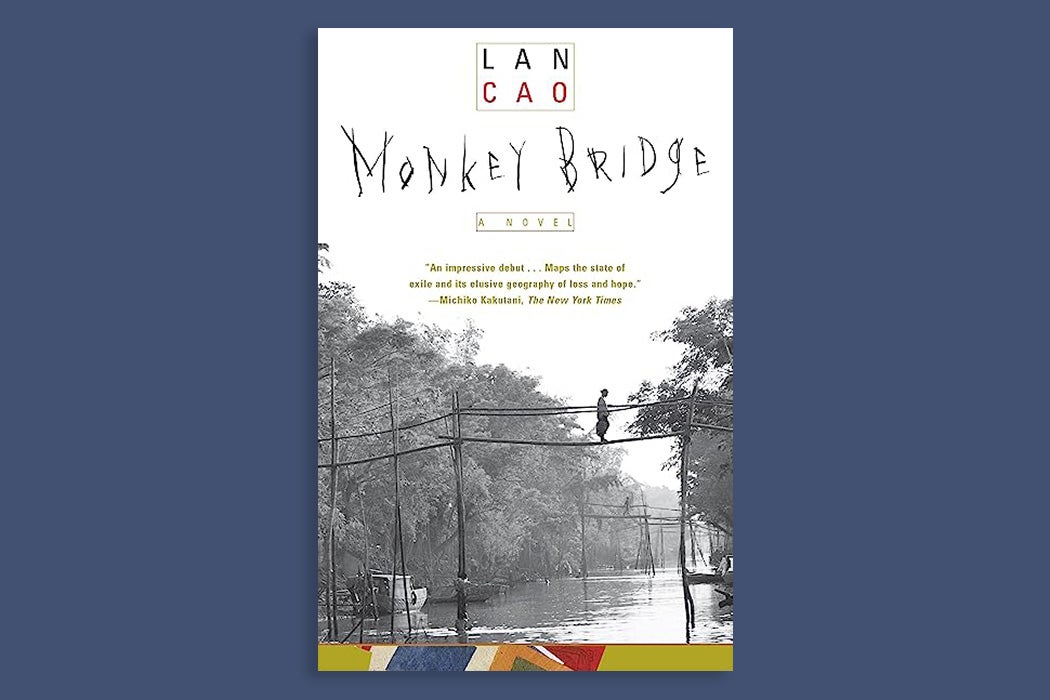

The Tricky Sentimentality of Lan Cao’s Monkey Bridge

You describe how, when applying for asylum, refugees are often required to provide simplified, inauthentic accounts of their experiences to evoke sympathy from and meet the expectations of immigration officers. Did you discover any meaningful differences between these accounts and the written works you analyze? Do the latter serve as a rejection or reclamation of the former?

Many refugee writers demonstrate awareness of the fact that telling stories serves ends both personal and pragmatic, therapeutic and bureaucratic. Their actual, personal stories are richer, more nuanced, less fixated on the facts and acts of brutality that give rise to displacement. They also recall joyful childhoods, loving families, memories of games and meals: small, transient things that evidence not so much suffering as its previous absence. The ordinary, the mundane often takes center stage, yet is rendered extraordinary insofar as they can never return to it. Asylum interviews are about fact checking, about producing evidence of direct persecution or violence, the immediacy of threat. Refugee writing, by contrast, textures, enriches, and humanizes these basic narratives of suffering; we are more than our suffering, they seem to say.

You also mention that accounts produced specifically for the asylum-seeking process tend to follow conventions of realist Western narratives, tied together with a clear “beginning, middle, and end.” Do you find that refugee writing, produced not to obtain asylum but to make sense of the experience itself, resists these conventions?

Oddly, they tend to be pretty standard in structure. Most run from childhood and pre-displacement to adulthood, maturity, and resettlement. I think this is because the tales themselves are so obliterated by destruction and trauma that, unlike the modernist aesthetic, no innovation is necessary to render them more extreme. James Joyce’s Dedalus has little real trauma beyond his own desires and tensions with the church; Mrs. Dalloway’s concerns about her party are beyond trivial and so formal innovation, fragmentation, and non-linear exposition add something to the telling. We don’t need that in stories about real suffering. But some, like Hassan Blasim [an Iraqi-born filmmaker and writer based in Finland and author of the 2020 novel God 99] do indeed offer narratives as atomized and eccentric as the tales they relate. Blasim, however, is a pointedly literary writer, schooled in both his native Arabic traditions and those of Western literature.

You cite Hannah Arendt’s view that modern legal protections are fundamentally contingent on citizenship. Yet, even after asylum is granted, many refugees remain second-class citizens, their perceived humanity far from ensured. In the writing you studied, how do authors deal with questions of identity, belonging, and security? Does refuge mark an endpoint—or simply the beginning of another leg in their endless journey?

There’s seemingly no end to being a refugee, to being displaced—to be re-settled is to be transplanted to a place that always remains, from food to music, topography to climate, alien. We see this perhaps most clearly in Nayeri’s The Ungrateful Refugee, in which the protagonist is always partly packed and ready to leave for the next temporary stay. Home is elusive. Language, too, is difficult: an aural signifier of difference retained in traces of accents. But we also see mutual cultural assimilation, which is perhaps more present in longer established diasporic communities, like those pushed around the world after the brutal 1947 partition of India and Pakistan. They begin, with time, to make the new space familiar and become accustomed to elements of that alien culture. Some begin to feel part of their adoptive home and to contribute to its political and cultural landscape.

How does contemporary refugee writing differ from writing that emerged from refugee crises of the previous century, which—as some of the academics you discuss note—played a key role in shaping the identity of modern literature, with its focus on displacement and estrangement?

Writing of the Jewish diaspora before and after World War II tended to be by established intellectuals and academics who became prominent advocates for the experience of post-war displacement. Many were also politically and theoretically trained—part of the Frankfurt School tradition, for example. I suspect also that there is more universal sympathy for the experience of those persecuted by the Nazis because this period forms such a core part of our own historical narrative—we liberated the camps, and therefore the suffering that took place there belongs somehow to our story in ways that the suffering of Middle Eastern, African, or Asian refugees does not. The Jewish people are also unique in that they have been perpetually displaced, and the post-war world united to refashion their homeland. Contemporary refugee writing from emerging nodal points of displacement events seem untethered to our own pasts, despite the fact that they are of course the product of colonization, decolonization, and proxy wars.

You note that many refugee writers and characters succumb to fatalism—the sense that “it is our destiny to be like this,” thrown across the world by historical and political forces far beyond their control. To what extent does refugee writing portray a genuine sense of recovery of agency?

In part by saying, “Thanks, but I’ll tell my own story”—one that’s embodied, fleshed out, given a nervous system. That said, to be displaced is to be object, material, pushed across borders, overloaded into boats, stuffed into unfit vehicles, herded over mountains by smugglers. The recovery usually begins in camps, when a degree of choice manifests in the most ordinary things. We see this in many texts: the refugee camp store acting as a kind of repository of memory and also offering some semblance of decision-making, however small. Everything a refugee does is through compulsion, necessity, urgency—they are in flight from something hostile towards something they hope is less so. Telling one’s story in one’s own understanding, reclaiming it, repositions refugees as actants and not just passive victims of violent historical currents.

You examine both fiction and memoir in your study. What are some of the key thematic or stylistic differences you observed between the two, even though—as you observe—they greatly influence one another?

They are remarkably similar in structure, themes, and even poetics. The same language figures in each, the same threats, means of evasion, forms of institutional hostility. That said, memoirs are more factual, and therefore more objective about the events they describe—even though they are written in first-person, they integrate historical facts in ways that can be more overt and less organic than fictions relating to the same events (think, for example, of books with child narrators). The other difference is that refugees who write fiction do not always write about their own experiences of displacement. Sometimes they do, as Abawi (the child of Afghan refugees, born in a German refugee camp) does when she writes A Land of Permanent Goodbyes, about Syrian refugees, but not always.

Weekly Newsletter

The chapters of From Rupture to Refuge are organized according to aforementioned coordinates, the different parts of a typical refugee’s journey—recalled home, conflict, panicked escape across borders, overpopulated refugee camps, refuge in a new country. On average, which of these parts is given the most weight by writers, and which the least?

I’d say refuge receives the littlest attention and hardly features at all in many works. Many in fact dwell on the refugee camp and never emerge from that place. We have some descriptions, including from Nayeri, but it’s less a subject than a place from which to reflect. I would say recalled home is the most recurrent and explored of the coordinates—present in each, returning at every stage: it’s the place from which they are displaced and remembered with inexhaustible fondness; it comes back when they flee and look back over their shoulder to the land they leave behind; it’s the thing destroyed by war; it’s the object of nostalgia and longing as they wait passively in refugee camps; and it’s the place against which host lands are measured.

What do you hope your book will contribute to both literary criticism and refugee studies?

There’s a huge amount of writing on Indian Diasporas and Jewish Diasporas, but very, very little on contemporary refugee literature, despite the fact that it’s becoming mainstream with displacement being the central issue of our era. We’ve seen studies beginning to emerge, but academics tend to look at established literary authors and their imaginative depiction of refugees instead of the texts I explore. My criteria here was writing by refugees or writing with a focus on refugee narrators. I hope to have introduced some new writers, writers that have received little or no attention for their work, though at least one of my subjects, Dinaw Mengestu, has already become a very significant author, having won the 2012 genius grant.