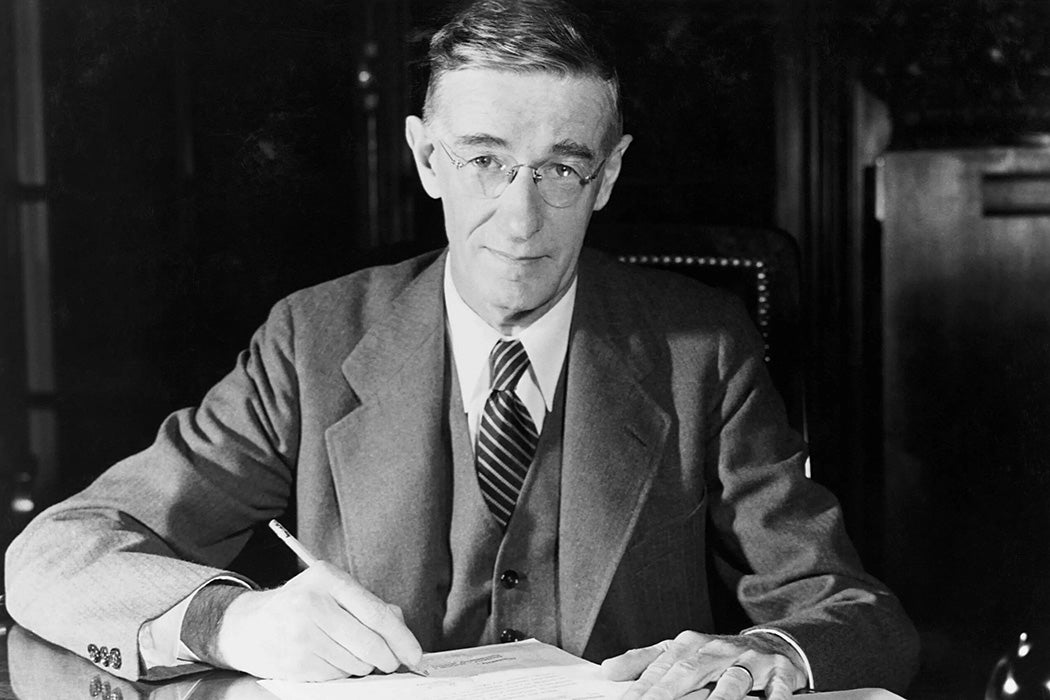

In 1941, American chemist James Conant referred to the Second World War as “a physicist’s war.” The phrase gained currency as fighting raged and science was mobilized in the form of new technologies like radar and the atomic bomb. As the war drew to a close, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt wrote a letter to his science adviser, Vannevar Bush, asking him to evaluate the place of science in the post-war world.

The result was Science: The Endless Frontier (1945), in which Bush called for the creation of a federal scientific agency. Deep in the report, he summarizes his diagnosis of a major problem.

“We have been living on our fat. For more than 5 years,” Bush writes,

many of our scientists have been fighting the war in the laboratories, in the factories and shops, and at the front…. Like troops, the scientists have been mobilized, and thrown into action to serve their country in time of emergency. But they have been diverted to a greater extent than is generally appreciated from the search for answers to the fundamental problems—from the search on which human welfare and progress depends. This is not a complaint—it is a fact.

Bush knew this because he played an outsized role in making it happen. He headed the Office of Scientific Research and Development during the war and enjoyed FDR’s unquestioning trust. In that role, Bush advanced major wartime research initiatives, including the Manhattan Project, which created the first atomic weapons.

As the person who reoriented science towards wartime applications looked ahead, he saw a bleak future if the country failed to demobilize and support the scientific community. Five years later, Congress created the National Science Foundation (NSF), a federal agency tasked to support scientific research.

But while Bush played an important role in making the NSF a reality, its final form departed enough from his vision that some historians think of it as a defeat. The story of the NSF’s creation is a winding political tale, but one worth starting with Science: The Endless Frontier, in which Bush articulates a philosophical and practical vision of science’s place in the United States. While many of his proposals didn’t make it into the final NSF bill, his argument helped shape a political consensus about the importance of science to national interests.

Bush explains that much of the science mobilized in the war came out of “basic research.” To him, this meant investigating fundamental scientific questions, regardless of potential applications. He writes that “scientific progress on a broad front results from the free play of free intellects, working on subjects of their own choice, in the manner dictated by their curiosity for exploration of the unknown.”

This wasn’t the sort of work that militaries or industry were usually willing to fund, which led the United States government to start funding scientific research after the Civil War. As Bush saw it, basic research still mainly happened at universities and colleges across the country, meaning that these institutions held the keys to America’s future health, safety, and prosperity.

But the endowments and private donations that funded university research were dwindling fast.

“To serve effectively as the centers of basic research these institutions must be strong and healthy,” Bush writes. Based on the reports of four committees, he constructed a blueprint for a federal agency designed to make this happen.

First, the United States needed to address an acute shortage of trained researchers and graduate students caused by the war. Bush warns that this would take a decade to fix but that his proposed agency could distribute scholarships and fellowships to develop a new generation of scientists. He thought the best way to sustain the work of this new, post-war generation was through grants given to the universities themselves. This would create the freedom necessary for basic research while providing stability for long-term projects. (This year, the Trump administration froze new NSF research grants and cancelled many existing grants).

Bush argues that the resulting research would provide “scientific capital,” creating “the fund from which the practical applications of knowledge must be drawn.” He believed that for a relatively modest investment, science could ensure that the United States became a long-term economic and military power. He wasn’t alone.

* * *

The Endless Frontier dropped into an existing discussion about science in the US that began in 1942. That year, Senator Harley M. Kilgore, a Democrat from West Virginia, proposed a federal science agency to Congress. He shared Bush’s instinct that science held the key to America’s future, but he differed on what a federal agency should look like.

Historian Daniel Kevles describes the Congressional battle that played out over the next eight years. Kilgore wanted a New Deal-type program for scientific research. He thought the agency should prioritize social and economic goals, and he hoped to weaken the ability of large businesses to abuse patent law. This was at odds with Bush’s view of basic research and the role of patents, but they shared some common ground.

“Bush was an anti-New Deal conservative,” Kevles explains, and was therefore skeptical of planning in scientific research. But he was also worried about the influence of monopolies, and didn’t believe they would fund basic research.

In 1944, Bush and Kilgore collaborated to draft a new bill, but Bush wasn’t satisfied with the result. It was at this moment that one of FDR’s lawyers suggested drafting the letter to Bush that prompted Science: The Endless Frontier, the writing of which allowed Bush to take more control over the process. Senator Warren Magnuson, a Democrat from Washington, proposed a competing bill in line with Bush’s vision, and Bush dropped support for Kilgore’s legislation. Neither got through Congress.

The problem wasn’t consensus over the need for an agency. In a 1945 hearing, only a single person expressed opposition to the idea. Belief in the urgent need to support scientific research crossed political lines. Despite this fact, various bills—including a Kilgore–Magnuson compromise bill—wove their way through Congress and ultimately failed.

One of the main sticking points—though not the only one—was presidential influence over the agency. Historian Jessica Wang explains that at the heart of the divide were competing approaches to technocracy, which split politicians and scientists. Bush’s proposed NSF leadership consisted of a committee of scientists, who would then select their director. The president could select the members of the committee but would have little influence over agency priorities.

By contrast, Kilgore and his allies wanted the NSF director to be a presidential appointment.

“Liberal and progressive-left scientists hoped to build a healthier relationship between science and society than that offered by either the national security state or Bush’s elite-driven conception of science policy,” Wang writes. They wanted the goals of the agency to stem from a democratic political will, and Presidential control was their method for achieving that.

Bush has been seen by contemporaries and historians as wanting to insulate science from politics. For his part, Bush stated in a 1947 Congressional testimony that “[t]he Foundation should…be fully responsible to the people, and this means to the Congress of the United States.” He argued that the agency should be subject to normal Executive procedures, aside from a select few regulations that he feared might inhibit the funding activity at the heart of its mission.

In the end, the president would determine the future of the NSF. When Bush finished Science: The Endless Frontier, he delivered it to the Executive Office as planned. But FDR had died earlier in the year, and The Endless Frontier landed on Harry Truman’s desk, where it received a colder response than Bush expected. In a paper describing Bush’s personal political network, Johnny Miri suggests that FDR’s death likely cost Bush his political influence. He’d already damaged his relationship with Kilgore, and he wasn’t on great terms with Truman or his administration, some members of which expressed skepticism at The Endless Frontier. In 1947, Republicans had a congressional majority for the first time in over a decade and passed a Bush-friendly version of the NSF bill. But it was up to Truman to sign it.

More to Explore

Origins of the UN: The US and USSR

On the advice of future NASA administrator James Webb and colleagues, Truman vetoed the bill. His administration wanted more presidential control over the NSF. Two more bills trickled through committees, until eventually Truman signed the final NSF bill in 1950.

Historians are divided over what the final bill meant for the interested parties. Kevles describes it as “largely a triumph for Bush,” since the functions of the agency mostly aligned with his original intentions. But Wang believes that the final bill “fell far short of the intentions of both the Bush and Kilgore camps.” It didn’t have Kilgore’s planning-oriented mission, the director was a presidential appointment, and the budget was vanishingly small.

Truman signed the bill in May. In June, the Korean War broke out. And while Congress had been slowly creeping toward a compromise, the defense establishment was hungry for scientific research.

* * *

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) and the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) had rapidly started funding university research after WWII, historian Roger Geiger explains. Scientists were divided about this, but they all shared a fear that outside interests might threaten their independence. Even the scientists who forged a relationship with the defense industry did so tentatively. They needed guarantees of independence, and early on, they mostly got them. The ONR became one of their largest funding sources in the immediate post-war years, and the money came with very few strings attached. Even the defense-skeptical Bush thought the early ONR provided a model for operating a civilian-run science agency, as did the NACA (the precursor to NASA).

But even without direct imposition, military influence grew as the NSF struggled to get its footing. The launch of Sputnik in 1957 exacerbated this but also gave the fledgling NSF stronger wings. The first NSF director Alan T. Waterman described what happened in a reflection on the NSF’s first ten years.

A National Research Council report in 1955 had painted a frightening picture, Waterman writes. It contained “sobering comparisons between the rates at which the United States and the Soviet Union were training scientists and technical manpower.” After the report, the NSF’s paltry initial budget rose to 16 million in 1956. But in 1957, it jumped to 40 million. By 1960, the NSF was receiving over 153 million dollars a year.

But the Cold War environment was not hospitable for all scientists. Fear of communism and “red-baiting” threatened many careers. Wang cites examples of liberal scientists in the 1950s who lost professorships and grants, were denied security clearances, and faced harassment from the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

In 1955, Bush, by then on the periphery of American politics, wrote an essay on the state of science in the country.

“Among scientific groups today there is sadness and discouragement,” he wrote, observing that there was no longer “mutual confidence and respect” between scientists, their government, and the military.

“The…question, as we try to envisage the future,” he wrote,

is whether this madness of ours is a passing phase, or whether it will grow until the free world transforms itself into a replica of the captive world it opposes. If the latter is the outcome, the struggle will be over, for it will then not matter which tyranny prevails.

* * *

Despite the rocky start, by 1960, Waterman put the NSF on a firm path forward. Waterman relied heavily on his advisory committee and spun up the research engine described in The Endless Frontier. The NSF funded scholarships, grants, and advanced university research facilities.

Waterman was aligned with the political consensus about the value of the agency—supporting universities and colleges was essential to him.

“The support of basic research is relatively inexpensive,” he wrote in his anniversary report, and “it is false economy to curtail the basic research that uncovers leads for future developments.”

Waterman would remain the NSF director under Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy.

After the 1960s, the NSF became one of the principal sources for basic research funding in the United States, along with agencies like the National Institutes of Health and NASA. While there have been disagreements about agency priorities, overall the NSF enjoyed broad support in the ensuing decades. In 1982, a split Congress voted to increase the NSF’s annual budget to over $1 billion for the first time. By 2023, its annual budget had increased to almost $9.9 billion—less than 0.2 percent of total federal spending that year.

Weekly Newsletter

Of this, the agency distributed over $1.3 billion to STEM education, with similar amounts going to math and physical sciences, computer science, and geosciences. Some areas of research are almost entirely funded by the NSF. While the budget was cut by half a billion dollars in 2024, the political consensus about the importance of funding scientific research remained largely intact for over eighty-plus years.

But since the beginning of 2025, agency activity has been disrupted. After grant payouts were temporarily frozen in January, about 10 percent of the agency’s staff was fired in February, with some being rehired weeks later. New grant funding slowed early in the year, while NSF fellowships for graduate students were cut in half. Then in late April, when grant freezes and cancellations began, the NSF director resigned as reports emerged that the agency’s funding and workforce could be halved in 2026.