The August 1936 picture of a shirtless King Edward VIII on holiday was, writes historian Ryan Linkof, the “first photograph in history to exhibit the unclothed body of a reigning British monarch for a mass audience.”

Suddenly the Emperor of India had no clothes, at least from the waist up. The image (view it in the article linked above) circulated worldwide, far beyond its original publication in the London tabloid Daily Sketch. That the topless king was pictured beside his married lover, Wallis Simpson, only added to the growing scandal. (King Edward would give up the throne to marry Simpson that December, making his one of the shortest reigns in British history.)

Linkof positions the taboo-breaking picture as fundamental to understanding how the photographic press reshaped “the way that the private activities of the British elite could be represented.” In fact, he argues that paparazzi photographers helped create the monarchy “that we have come to know, occupying a space somewhere between the mythologized stratosphere of royalist lore and the mundanely human reality of the physical body.”

Since the medieval period, the European monarch’s body was conceived as encompassing both the sacred and the profane. The sacredness was where sovereignty lay, and it was part of the strange idea that kingship was inheritable. But the less said about the profane, the merely human body, the better. This had to be hidden, covered up by the sumptuous “vestments and regalia [that] have been central to the consolidation of royal power, privilege, and grandeur.” But behind or underneath these very public bodies, there was obviously real flesh and real blood, the things heir to, as Hamlet said “a thousand natural shocks”—and camera flashes.

“To view the unclothed body of the monarch, by contrast, is to see behind the pomp, ceremony, and mythology of monarchy,” stresses Linkof. Edward without a crown or tuxedo, it turned out, was just a playboy sort of chappie in a pedal canoe with a pet dog in his lap and his best girlie by his side.

Daily Sketch photographer Stanley Devon got the fateful picture by using a “rudimentary” telephoto lens from an airplane he chartered to chase after the royal boating party off the Cote d’Azur. The resulting image, from a diving plane, was shaky and not perfectly focused. Such frozen stolen glances, as it were, would come to define authenticity in tabloid photographs of celebrities caught in the act.

More to Explore

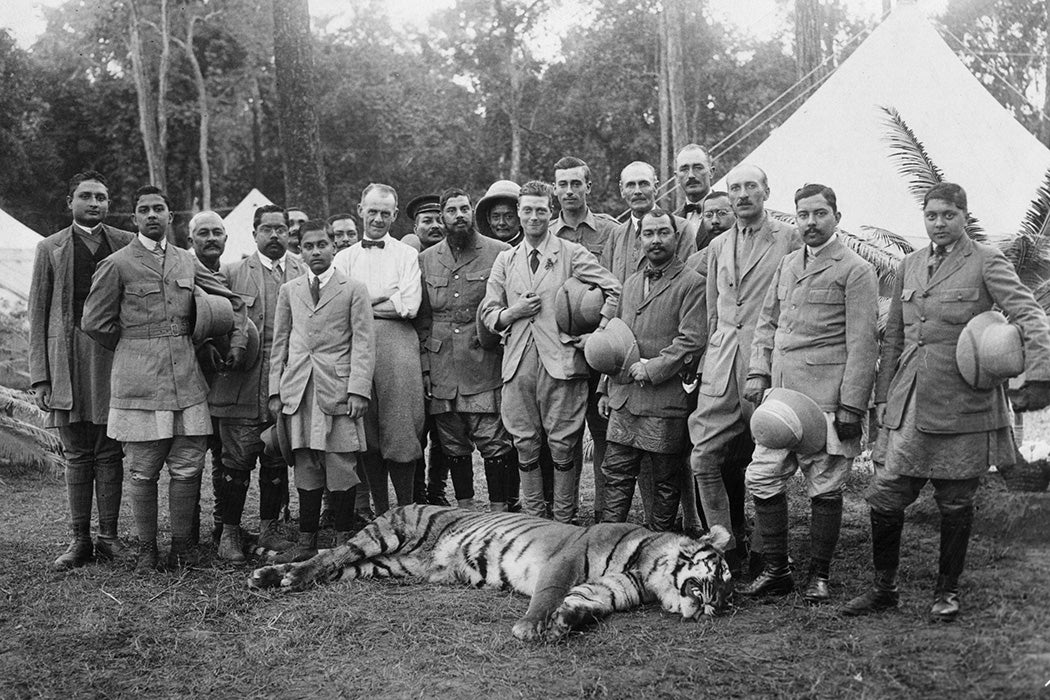

The Prince of Wales’ 1921 Trip to India Was a Royal Disaster

Photos of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton vacationing off Ischia in 1962 are considered by some to be the first paparazzi photographs, but the enterprising Devon was at it long before that. Celebrity voyeurism was a commodity decades before the coining of the term “paparazzi,” which is an eponym from the celebrity-photog Paparazzo in Frederico Fellini’s 1960 film about the soulless desperation of the Jet Set, La Dolce Vita. Devon was a direct ancestor of the paparazzi, including the ones chasing the vehicle carrying Diana, Princess of Wales, when it crashed and killed her, her lover, and their driver in August 1997. (Topless shots of Diana also churned through the tabloid mill.)

“The press coverage of the [Edward/Wallis] affair crystallized a new form of visual culture that transformed the social world of Britain’s wealthiest and most powerful people—the royals chief among them—into media spectacled consumed by mass audiences,” writes Linkof.

Weekly Newsletter

Edward’s father, George V, was a grandson of Queen Victoria, perhaps the epitome of the fully clothed monarch; she wore mourning dress for forty years. George V told his playboy son that “a Prince should not show himself too much. The Monarchy must remain on a pedestal.” George V also did his best to keep the growing number of photographs of Prince Edward and his scandalous lady friend out of the news. But once George was dead and Edward was king, the cat was out of the bag.

“Photographers pursued the couple relentlessly,” writes Linkof. This pursuit continued post-throne as the newly titled “Duke and Duchess of Windsor” became charter members of High Society, objects of fascination for decades until their deaths in the 1970s and 1980s.

After their marriage in 1937, Edward and Wallis toured Nazi Germany in an unofficial capacity, against the advice of the British government. There, Hitler and company treated the pair like royalty, just as the two of them felt they deserved.

![A Chelsea Pensioner, wearing a sprig of orange blossom [?] in his buttonhole, sipping a dish of tea. Engraving by J. Jenkins after M. W. Sharp, 1840](https://daily-jstor-org.bibliotheek.ehb.be/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/consuming_the_empire_alt_1050x700-600x400.jpg)